PART I.

The Gaboon River and Gorilla Land.

“It was my hint to speak, such was my process;

And of the cannibals that each other eat,

The anthropophagi, and men whose heads

Do grow beneath their

Shoulders.”–Othello.

Part I.

Trip to Gorilla Land.

Chapter I.

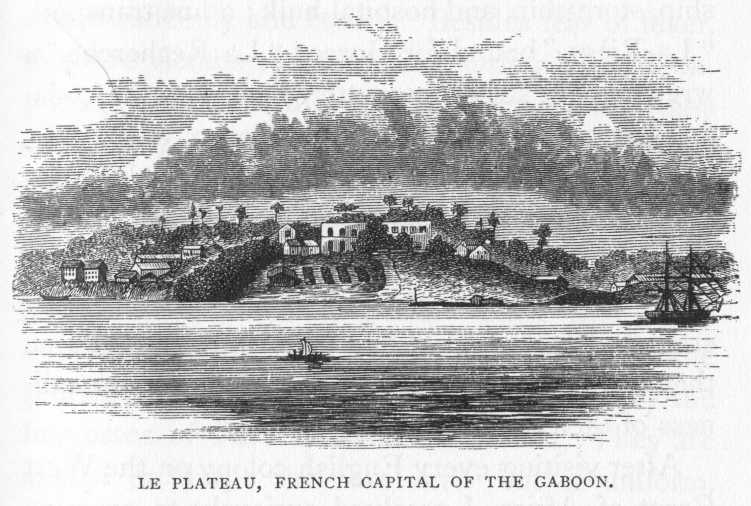

Landing at the Rio Gabão (Gaboon River).—le Plateau, the French Colony.

I remember with lively pleasure my first glance at the classic stream of the “Portingal Captains” and the “Zeeland interlopers.” The ten-mile breadth of the noble Gaboon estuary somewhat dwarfed the features of either shore as we rattled past Cape Santa Clara, a venerable name, “‘verted” to Joinville. The bold northern head, though not “very high land,” makes some display, because we see it in a better light; and its environs are set off by a line of scattered villages. The vis-a-vis of Louis Philippe Peninsula on the starboard bow (Zuidhoeck), “Sandy Point” or Sandhoeck, by the natives called Pongára, and by the French Péninsule de Marie–Amélie, shows a mere fringe of dark bristle, which is tree, based upon a broad red-yellow streak, which is land. As we pass through the slightly overhung mouth, we can hardly complain with a late traveller of the Gaboon’s “sluggish waters;” during the ebb they run like a mild mill-race, and when the current, setting to the north-west, meets a strong sea-breeze from the west, there is a criss-cross, a tide-rip, contemptible enough to a cruizer, but quite capable of filling cock-boats. And, nearing the end of our voyage, we rejoice to see that the dull down-pourings and the sharp storms of Fernando Po have apparently not yet migrated so far south. Dancing blue wavelets, under the soft azure sky, plash and cream upon the pure clean sand that projects here and there black lines of porous ironstone waiting to become piers; and the water-line is backed by swelling ridges, here open and green-grassed, there spotted with islets of close and shady trees. Mangrove, that horror of the African voyager, shines by its absence; and the soil is not mud, but humus based on gravels or on ruddy clays, stiff and retentive. The formation, in fact, is everywhere that of Eyo or Yoruba, the goodly region lying west of the lower Niger, and its fertility must result from the abundant water supply of the equatorial belt.

The charts are fearful to look upon. The embouchure, well known to old traders, has been scientifically surveyed in our day by Lieutenant Alph. Fleuriot de Langle, of La Malouine (1845), and the chart was corrected from a survey ordered by Capitaine Bouët-Willaumez (1849); in the latter year it was again revised by M. Charles Floix, of the French navy, and, with additions by the officers of Her Britannic Majesty’s service, it becomes our No. 1877. The surface is a labyrinth of banks, rocks, and shoals, “Ely,” “Nisus,” “Alligator,” and “Caraibe.” In such surroundings as these, when the water shallows apace, the pilot must not be despised.

Her Majesty’s steam-ship “Griffon,” Commander Perry, found herself, at 2 P.M. on Monday, March, 17, 1862, in a snug berth opposite Le Plateau, as the capital of the French colony is called, and amongst the shipping of its chief port, Aumale Road. The river at this neck is about five miles broad, and the scene was characteristically French. Hardly a merchant vessel lay there. We had no less than four naval consorts “La Caravane,” guard-ship, store-ship, and hospital-hulk; a fine transport, “La Riège,” bound for Goree; “La Recherche,” a wretched old sailing corvette which plies to Assini and Grand Basam on the Gold Coast; and, lastly, “La Junon,” chef de division Baron Didelot, then one of the finest frigates in the French navy, armed with fifty rifled sixty-eight pounders. It is curious that, whilst our neighbours build such splendid craft, and look so neat and natty in naval uniform, they pay so little regard to the order and cleanliness of their floating homes.

After visiting every English colony on the West Coast of Africa, I resolved curiously to examine my first specimen of our rivals, the “principal centre of trade in western equatorial Africa.” The earliest visit—in uniform, of course—was to Baron Didelot, whose official title is “Commandant Supérieur des Établissements de la Côte d’Or et du Gabon;” the following was to M. H. S. L’Aulnois, “Lieutenant de Vaisseau et Commandant Particulier du Comptoir de Gabon.” These gentlemen have neat bungalows and gardens; they may spend their days ashore, but they are very careful to sleep on board. All the official whites appear to have a morbid horror of the climate; when attacked by fever, they “cave in” at once, and recovery can hardly be expected. This year also, owing to scanty rains, sickness has been rife, and many cases which began with normal mildness have ended suddenly and fatally. Besides fear of fever, they are victims to ennui and nostalgia; and, expecting the Comptoir to pay large profits, they are greatly disappointed by the reverse being the case.

But how can they look for it to be otherwise? The modern French appear fit to manage only garrisons and military posts. They will make everything official, and they will not remember the protest against governing too much, offered by the burgesses of Paris to Louis le Grand. They are always on duty; they are never out of uniform, mentally and metaphorically, as well as bodily and literally. Nothing is done without delay, even in the matter of signing a ship’s papers. A long procès-verbal takes the place of our summary punishment, and the gros canon is dragged into use on every occasion, even to enforce the payment of native debts.

In the Gaboon, also, there is a complication of national jealousy, suggesting the mastiff and the poodle. A perpetual war rages about flags. English craft may carry their colours as far up stream as Coniquet Island; beyond this point they must either hoist a French ensign, or sail without bunting—should the commodore permit. Otherwise they will be detained by the commander of the hulk “l’Oise,” stationed at Anenge-nenge, some thirty-eight to forty miles above Le Plateau. Lately a Captain Gordon, employed by Mr. Francis Wookey of Taunton, was ordered to pull down his flag: those who know the “mariner of England” will appreciate his feelings on the occasion. Small vessels belonging to foreigners, and employed in cabotage, must not sail with their own papers, and even a change of name is effected under difficulties. About a week before my arrival a certain pan-Teutonic Hamburgher, Herr B—, amused himself, after a copious breakfast, with hoisting and saluting the Union Jack, in honour of a distinguished guest, Major L—. report was at once spread that the tricolor had been hauled down “with extreme indignity;” and the Commodore took the trouble to reprimand the white, and to imprison “Tom Case,” the black in whose town the outrage had been allowed.

This by way of parenthesis. My next step was to request the pleasure of a visit from Messrs. Hogg and Kirkwood, who were in charge of the English factories at Glass Town and Olomi; they came down stream at once, and kindly acted as ciceroni around Le Plateau. The landing is good; a reef has been converted into a jetty and little breakwater; behind this segment of a circle we disembarked without any danger of being washed out of the boat, as at S’a Leone, Cape Coast Castle, and Accra. Unfortunately just above this pier there is a Dutch-like jardin d’été—beds of dirty weeds bordering a foul and stagnant swamp, while below the settlement appears a huge coal-shed: the expensive mineral is always dangerous when exposed in the tropics, and some thirty per cent. would be saved by sending out a hulk. The next point is the Hotel and Restaurant Fischer—pronounced Fi-cherre, belonging to an energetic German–Swiss widow, who during six years’ exile had amassed some 65,000 francs. In an evil hour she sent a thieving servant before the “commissaire de police;” the negress escaped punishment, but the verandah with its appurtenances caught fire, and everything, even the unpacked billiard-table, was burnt to ashes. Still, Madame the Brave never lost heart. She applied herself valiantly as a white ant to repairing her broken home, and, wonderful to relate in this land of no labour, ruled by the maxim “festina lente,” all had been restored within six months. We shall dine at her table d’hôte.

Our guide led up and along the river bank, where there is almost a kilometre of road facing six or seven kilometres of nature’s highway—the stream. The swampy jungle is not cleared off from about the Comptoir, and presently the perfume of the fat, rank weeds; and the wretched bridges, a few planks spanning black and fetid mud, drove us northwards or inland, towards the neat house and grounds of the “Commandant Particulier.” The outside walls, built in grades with the porous, dark-red, laterite-like stone dredged from the river, are whitewashed with burnt coralline and look clean; whilst the house, one of the best in the place, is French, that is to say, pretty. Near it is a cluster of native huts, mostly with walls of corded bamboo, some dabbed with clay and lime, and all roofed with the ever shabby-looking palm-leaf; none are as neat as those of the “bushmen” in the interior, where they are regularly and carefully made like baskets or panniers. The people appeared friendly; the men touched their hats, and the women dropped unmistakably significant curtsies.

After admiring the picturesque bush and the natural avenues behind Le Plateau, we diverged towards the local Père-la-Chaise. The new cemetery, surrounded by a tall stone wall and approached by a large locked gate, contains only four tombs; the old burial ground opposite is unwalled, open, and painfully crowded; the trees have run wild, the crosses cumber the ground, the gravestones are tilted up and down; in fact the foul Golgotha of Santos, São Paulo, the Brazil, is not more ragged, shabby, and neglected. We were shown the last resting-place of M. du Chaillu pere, agent to Messrs. Oppenheim, the old Parisian house: he died here in 1856.

Resuming our way parallel with, but distant from the river, we passed a bran-new military storehouse, bright with whitewash. Outside the compound lay the lines of the “Zouaves,” some forty negroes whom Goree has supplied to the Gaboon; they were accompanied by a number of intelligent mechanics, who loudly complained of having been kidnapped, coolie-fashion. We then debouched upon Fort Aumale; from the anchorage it appears a whitewashed square, whose feet are dipped in bright green vegetation, and its head wears a dingy brown roof-thatch. A nearer view shows a pair of semi-detached houses, built upon arches, and separated by a thoroughfare; the cleaner of the two is a hospital; the dingier, which is decorated with the brown-green stains, the normal complexion of tropical masonry, lodges the station Commandant and the medical officers. Fronting the former and by the side of an avenue that runs towards the sea is an unfinished magazine of stone, and to the right, as you front the sun, lies the garden of the “Commandant du Comptoir,” choked with tropical weeds. Altogether there is a scattered look about the metropolis of the “Gabon,” which numbers one foot of house to a thousand of “compound.”

Suddenly a bonnet like a pair of white gulls wings and a blue serge gown fled from us, despite the weight of years, like a young gazelle; the wearer was a sister of charity, one of five bonnes sœurs. Their bungalow is roomy and comfortable, near a little chapel and a largish school, whence issue towards sunset the well-known sounds of the Angelus. At some distance down stream and on the right or northern bank lies a convent, and a house superintended by the original establisher of the mission in 1844, the bishop, Mgr. Bessieux, who died in 1872, aged 70. There are extensive plantations, but the people are too lazy to take example from them.

Before we hear the loud cry à table, we may shortly describe the civilized career of the Gaboon. In 1842, when French and English rivalry, burning hot on both sides of the Channel, extended deep into the tropics and spurned the equator, and when every naval officer, high and low, went mad about concluding treaties and conquering territory on paper, France was persuaded to set up a naval station in Gorilla-land. The northern and the southern shore each had a king, whose consent, after a careless fashion, was considered decorous. His Majesty of the North was old King Glass1 and his chief “tradesman,” that is, his premier, was the late Toko, a shrewd and far-seeing statesman. His Majesty of the South was Rapwensembo, known to the English as King William, to the French as Roi Denis.

Matters being in this state, M. le Comte Bouët-Willaumez, then Capitaine de Vaisseau and Governor of Senegal, resolved, coûte que coûte, to have his fortified Comptoir. Evidently the northern shore was preferable; it was more populous and more healthy, facing the fresh southerly winds. During the preliminary negotiations Toko, partial to the English, whose language he spoke fluently, and with whom the Glass family had ever been friendly, thwarted the design with all his might, and, despite threats and bribes, honestly kept up his opposition to the last. Roi Denis, on the other hand, who had been decorated with the Légion d’Honneur for saving certain shipwrecked sailors, who knew French well, and who hoped to be made king of the whole country, favoured to the utmost Gallic views, taking especial care, however, to place the broad river between himself and his white friends. M. de Moleon, Capitaine de Frégate, and commanding the brig “Le Zèbre,” occupied the place, Mr. Wilson2(“Western Africa,” p. 254) says by force of arms, but that is probably an exaggeration. To bring our history to an end, the sons of Japheth overcame the children of Ham, and, as the natives said, “Toko he muss love Frenchman, all but out of (anglicè ‘in’) his heart.”

As in the streets of Paris, so in every French city at home and abroad,

“Verborum vetus interit ætas,”

and an old colonial chart often reads like a lesson in modern history. Here we still find under the Empire the Constitutional Monarchy of 1842–3. Mount Bouët leads to Fort “Aumale:” Point Joinville, at the north jaw of the river, faces Cap Montagnies: Parrot has become “Adelaide,” and Coniquet “Orleans” Island. Indeed the love of Louis–Philippe’s family has lingered in many a corner where one would least expect to meet it, and in 1869 I found “Port Saeed” a hot-bed of Orleanism.

The hotel verandah was crowded with the minor officials, the surgeons, and the clerks of the comptoir, drinking absinthe and colicky vermouth, smoking veritable “weeds,” playing at dominoes, and contending who could talk longest and loudest. At 7 P.M. the word was given to “fall to.” The room was small and exceedingly close; the social board was big and very rickety. The clientèle rushed in like backwoodsmen on board a Mississippi floating-palace, stripped off their coats, tucked up their sleeves, and, knife in one hand and bread in the other, advanced gallantly to the fray. They began by quarrelling about carving; one made a sporting offer to découper la soupe, but he would go no farther; and Madame, as the head of the table, ended by asking my factotum, Selim Agha, to “have the kindness.” The din, the heat, the flare of composition candles which gave 45 per cent. less of light than they ought, the blunders of the slaves, the objurgations of the hostess, and the spectacled face opposite me, were as much as I could bear, and a trifle more. No wonder that the resident English merchants avoid the table-d’hôte.

Provisions are dear and scarce at the Gaboon, where, as in other parts of West Africa, the negro will not part with his animals, unless paid at the rate of some twenty-two or twenty-three shillings for a lean goat or sheep. Yet the dinner is copious; the employés contribute, their rations; and thus the table shows beef twice a week. Black cattle are imported from various parts of the coast, north and south; perhaps those of the Kru country stand the climate best; the Government yard is well stocked, and the polite Commodore readily allows our cruizers to buy bullocks. Madame also is not a “bird with a long bill;” the dinner, including piquette, alias vin ordinaire, coffee, and the petit verre, costs five francs to the stranger, and one franc less pays the déjeuner a la fourchette—most men here eat two dinners. The soi-disant Médoc (forty francs per dozen) is tolerable, and the cassis (thirty francs) is drinkable. I am talking in the present of things twelve years past. What a shadowy, ghostly table d’hôte it has now become to me!

After dinner appeared cigar and pipe, which were enjoyed in the verandah: I sat up late, admiring the intense brilliancy of the white and blue lightning, but auguring badly for the future,— natives will not hunt during the rains. A strong wind was blowing from the north-east, which, with the north-north-east, is here, as at Fernando Po and Camaronen, the stormy quarter. A “dry tornado,” however, was the only result that night.

My trip to Gorilla-land was limited by the cruise upon which H.M.S.S. “Griffon” had been ordered, namely, to and from the South Coast with mail-bags. Many of those whom I had wished to see were absent; but Mr. Hogg set to work in the most business-like style. He borrowed a boat from the Rev. William Walker, of the Gaboon Mission, who kindly wrote that I should have something less cranky if I could wait awhile; he manned it with three of his own Krumen, and he collected the necessary stores and supplies of cloth, pipes and tobacco, rum, white wine, and absinthe for the natives.

My private stores cost some 200 francs. They consisted of candles, sugar, bread, cocoa, desiccated milk, and potatoes; Cognac and Médoc; ham, sausages, soups, and preserved meats, the latter French and, as usual, very good and very dear. The total expenditure for twelve days was 300 francs.

My indispensables were reduced to three loads, and I had four “pull-a-boys,” one a Mpongwe, Mwáká alias Captain Merrick, a model sluggard; and Messrs. Smoke, Joe Williams, and Tom Whistle—Kru-men, called Kru-boys. This is not upon the principle, as some suppose, of the grey-headed post-boy and drummer-boy: all the Kraoh tribes end their names in bo, e.g. Worebo, from “wore,” to capsize a canoe; Grebo, from the monkey “gre” or “gle;” and many others. Bo became “boy,” even as Sipahi (Sepoy) became Sea-pie, and Sukhani (steersman) Sea–Coney.

Gaboon is French, with a purely English trade. Gambia is English, with a purely French trade; the latter is the result of many causes, but especially of the large neighbouring establishments at Goree, Saint Louis de Sénégal, and Saint Joseph de Galam. Exchanging the two was long held the soundest of policy. The French hoped by it to secure their darling object,—exclusive possession of the maritime regions, as well as the interior, leading to the gold mines of the Mandengas (Mandingas), and allowing overland connection with their Algerine colony. The English also seemed willing enough to “swop” an effete and dilapidated settlement, surrounded by more powerful rivals—a hot-bed of dysentery and yellow fever, a blot upon the fair face of earth, even African earth—for a new and fresh country, with a comparatively good climate, in which the thermometer ranges between 65° (Fahr.) and 90°, with a barometer as high as the heat allows; and where, being at home and unwatched, they could subject a lingering slave-trade to a regular British putting-down. But, when matters came to the point in 1870–71, the proposed bargain excited a storm of sentimental wrath which was as queer as unexpected. The French object to part with the Gaboon, as the Germans appear inclined to settle upon the Ogobe River. In England, cotton, civilization, and even Christianity were thrust forward by half-a-dozen merchants, and by a few venal colonial prints. The question assumed the angriest aspect; and, lastly, the Prussian–French war underwrote the negotiations with a finis pro temp. I hope to see them renewed; and I hope still more ardently to see the day when we shall either put our so-called “colonies” on the West Coast of Africa to their only proper use, convict stations, or when, if we are determined upon consuming our own crime at home, we shall make up our minds to restore them to the negro and the hyaena, their “old inhabitants.”

At the time of my visit, the Gaboon River had four English traders; viz.

1. Messrs. Laughland and Co., provision-merchants, Fernando Po and Glasgow. Their resident agent was Mr. Kirkwood.

2. Messrs. Hatton and Cookson, general merchants, Liverpool. Their chief agent, Mr. R.B.N. Walker, who had known the river for eleven years (1865), had left a few days before my arrival; his successor, Mr. R.B. Knight, had also sailed for Cape Palmas, to engage Kru-men, and Mr. Hogg had been left in charge.

3. Messrs. Wookey and Dyer, general merchants, Liverpool. Agents, Messrs. Gordon and Bryant.

4. Messrs. Bruford and Townsend, of Bristol. Agent, Captain Townsend.

The resident agents for the Hamburg houses were Messrs. Henert and Bremer.

The English traders in the Gaboon are nominally protected by the Consulate of Sao Paulo de Loanda, but the distance appears too great for consul or cruizer. They are naturally anxious for some support, and they agitate for an unpaid Consular Agent: at present they have, in African parlance, no “back.” A Kruman, offended by a ration of plantains, when he prefers rice, runs to the Plateau, and lays some fictitious complaint before the Commandant. Monsieur summons the merchant, condemns him to pay a fine, and dismisses the affair without even permitting a protest. Hence, impudent robbery occurs every day. The discontent of the white reacts upon his clients the black men; of late, les Gabons, as the French call the natives, have gone so far as to declare that foreigners have no right to the upper river, which is all private property. The line drawn by them is at Fetish Rock, off Pointe Française, near the native village of Mpíra, about half a mile above the Plateau; and they would hail with pleasure a transfer to masters who are not so uncommonly ready with their gros canons.

The Gaboon trade is chronicled by John Barbot, Agent–General of the French West African Company, “Description of the Coast of South Guinea,” Churchill, vol. v. book iv. chap. 9; and the chief items were, and still are, ivory and beeswax. Of the former, 90,000 lbs. may be exported when the home prices are good, and sometimes the total has reached 100 tons. Hippopotamus tusks are dying out, being now worth only 2s. per lb. Other exports are caoutchouc, ebony (of which the best comes from the Congo), and camwood or barwood (a Tephrosia). M. du Chaillu calls it the “Ego-tree;” the natives (Mpongwe) name the tree Igo, and the billet Ezígo.

1 Paul B. du Chaillu, Chap. III. “Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa.” London: Murray, 1861.

2 Rev. J. Leighton Wilson of the Presbyterian Mission, eighteen years in Africa, “Western Africa,” &c. New York. Harpers, 1856.