Chapter II.

The Departure.—the Tornado.—arrival at “The Bush.”

I set out early on March 19th, a day, at that time, to me the most melancholy in the year, but now regarded with philosophic indifference. A parting visit to the gallant “Griffons,” who threw the slipper, in the shape of three hearty cheers and a “tiger,” wasted a whole morning. It was 12.30 P.M. before the mission boat turned her head towards the southern bank, and her crew began to pull in the desultory manner of the undisciplined negro.

The morning had been clear but close, till a fine sea breeze set in unusually early. “The doctor” seldom rises in the Gaboon before noon at this season; often he delays his visit till 2 P.M., and sometimes he does not appear at all. On the other hand, he is fond of late hours. Before we had progressed a mile, suspicious gatherings of slaty-blue cloud-heaps advanced from the north-east against the wind, with a steady and pertinacious speed, showing that mischief was meant. The “cruel, crawling sea” began to rough, purr, and tumble; a heavy cross swell from the south-west dandled the up-torn mangrove twigs, as they floated past us down stream, and threatened to swamp the deeply laden and cranky old boat, which was far off letter A1 of Lloyd’s. The oarsmen became sulky because they were not allowed to make sail, which, in case of a sudden squall, could not have been taken in under half an hour. Patience! Little can be done, on the first day, with these demi-semi-Europeanized Africans, except to succeed in the inevitable trial of strength.

The purple sky-ground backing the Gaboon’s upper course admirably set off all its features. Upon the sea horizon, where the river measures some thirty miles across, I could distinctly see the junction of the two main branches, the true Olo’ Mpongwe, the main stream flowing from the Eastern Ghats, and the Rembwe (Ramboue) or south-eastern influent. At the confluence, tree-dots, tipping the watery marge, denoted what Barbot calls the “Pongo Islands.” These are the quoin-shaped mass “Dámbe” (Orleans Island) alias “Coniquet” (the Conelet), often corrupted to Konikey; the Konig Island of the old Hollander,3 and the Prince’s Island of the ancient Briton. It was so called because held by the Mwáni-pongo, who was to this region what the Mwáni-congo was farther south. The palace was large but very mean, a shell of woven reeds roofed with banana leaves: the people, then mere savages, called their St. James’ “Goli-patta,” or “Royal House,” in imitation of a more civilized race near Cape Lopez. The imperial islet is some six miles in circumference; it was once very well peopled, and here ships used to be careened. The northern point which starts out to meet it is Ovindo (Owëendo of old), alias Red Point, alias “Rodney’s,” remarkable for its fair savannah, of which feature more presently. In mid-stream lies Mbini (Embenee), successively Papegay, Parrot—there is one in every Europeo–African river—and Adelaide Island.

Between Ovindo Point, at the northern bend of the stream, stand the so-called “English villages,” divided from the French by marshy ground submerged during heavy rains. The highest upstream is Olomi, Otonda-naga, or town of “Cabinda,” a son of the late king. Next comes Glass Town, belonging to a dynasty which has lasted a century—longer than many of its European brethren. In 1787 a large ship-bell was sent as a token of regard by a Bristol house, Sydenham and Co., to an old, old “King Glass,” whose descendants still reign. Olomi and Glass Town are preferred by the English, as their factories catch the sea-breeze better than can Le Plateau: the nearer swamps are now almost drained off, and the distance from the “authorities” is enough for comfort. Follow Comba (Komba) and Tom Case, the latter called after Case Glass, a scion of the Glasses, who was preferred as captain’s “tradesman” by Captain Vidal, R.N., in 1827, because he had “two virtues which rarely fall to the lot of savages, namely, a mild, quiet manner, and a low tone of voice when speaking.” Tom Qua Ben, justly proud of the “laced coat of a mail coach guard,” was chosen by Captain Boteler, R.N. The list concludes with Butabeya, James Town, and Mpira.

These villages are not built street-wise after Mpongwe fashion. They are scatters of shabby mat-huts, abandoned after every freeman’s death; and they hardly emerge from the luxuriant undergrowth of manioc and banana, sensitive plant and physic nut (Jatropha Curcas), clustering round a palm here and there. Often they are made to look extra mean by a noble “cottonwood,” or Bombax (Pentandrium), standing on its stalwart braces like an old sea-dog with parted legs; extending its roots over a square acre of soil, shedding filmy shade upon the surrounding underwood, and at all times ready, like a certain chestnut, to shelter a hundred horses.

Between the Plateau and Santa Clara, beginning some two miles below the former, are those hated and hating rivals, Louis Town, Qua Ben, and Prince Krinje, the French settlements. The latter is named after a venerable villain who took in every white man with whom he had dealings, till the new colony abolished that exclusive agency, that monopoly so sacred in negro eyes, which here corresponded with the Abbánat of the Somal. Mr. Wilson (p. 252) recounts with zest a notable trick played by this “little, old, grey-headed, humpback man” upon Captain Bouët-Willaumez, and Mr. W. Winwood Reade (chap, xi.) has ably dramatized “Krinji, King George and the Commandant.” On another occasion, the whole population of the Gaboon was compelled by a French man-o-war to pay “Prince Cringy’s” debts, and he fell into disfavour only when he attempted to wreck a frigate by way of turning an honest penny.

But soon we had something to think of besides the view. The tumultuous assemblage of dark, dense clouds, resting upon the river-surface in our rear, formed line or rather lines, step upon step, and tier on tier. While the sun shone treacherously gay, a dismal livid gloom palled the eastern sky, descending to the watery horizon; and the estuary, beneath the sable hangings which began to depend from the cloud canopy, gleamed with a ghastly whitish green. Distant thunders rumbled and muttered, and flashes of the broadest sheets inclosed fork and chain lightning; the lift-fire zigzagged in tangled skeins here of chalk-white threads, there of violet wires, to the surface of earth and sea. Presently nimbus-step, tier and canopy, gradually breaking up, formed a low arch regular as the Bifröst bridge which Odin treads, spanning a space between the horizon, ninety degrees broad and more. The sharply cut soffit, which was thrown out in darkest relief by the dim and sallow light of the underlying sky, waxed pendent and ragged, as though broken by a torrent of storm. What is technically called the “ox-eye,” the “egg of the tornado,” appeared in a fragment of space, glistening below the gloomy rain-arch. The wind ceased to blow; every sound was hushed as though Nature were nerving herself, silent for the throe, and our looks said, “In five minutes it will be down upon us.” And now it comes. A cold blast smelling of rain, and a few drops or rather splashes, big as gooseberries and striking with a blow, are followed by a howling squall, sharp and sudden puffs, pulsations and gusts; at length a steady gush like a rush of steam issues from that awful arch, which, after darkening the heavens like an eclipse, collapses in fragmentary torrents of blinding rain. In the midst of the spoon-drift we see, or we think we see, “La Junon” gliding like a phantom-ship towards the river mouth. The lightning seems to work its way into our eyes, the air-shaking thunder rolls and roars around our very ears; the oars are taken in utterly useless, the storm-wind sweeps the boat before it at full speed as though it had been a bit of straw. Selim and I sat with a large mackintosh sheet over our hunched backs, thus offering a breakwater to the waves; happily for us, the billow-heads were partly cut off and carried away bodily by the raging wind, and the opened fountains of the firmament beat down the breakers before they could grow to their full growth. Otherwise we were lost men; the southern shore was still two miles distant, and, as it was, the danger was not despicable. These tornadoes are harmless enough to a cruiser, and under a good roof men bless them. But H.M.S. “Heron” was sunk by one, and the venture of a cranky gig laden ŕ fleur d’eau is what some call “tempting Providence.”

Stunned with thunder, dazzled by the vivid flashes of white lightning, dizzy with the drive of the boat, and drenched by the torrents and washings from above and below, we were not a little pleased to feel the storm-wind slowly lulling, as it had cooled the heated regions ahead, and to see the sky steadily clearing up behind, as the blackness of the cloud, rushing with racer speed, passed over and beyond us. The increasing stillness of the sea raised our spirits;

“For nature, only loud when she destroys,

Is silent when she fashions.”

But the storm-demon’s name is “Tornado” (Cyclone): it will probably veer round to the south, where, meeting the dry clouds that are gathering and massing there, it will involve us in another fray. Meanwhile we are safe, and as the mist clears off we sight the southern shore. The humbler elevation, notably different from the northern bank, is dotted with villages and clearings. The Péninsula de Marie–Amélie, alias “Round Corner,” the innermost southern point visible from the mouth, projects to the north-north-east in a line of scattered islets at high tides, ending in Le bois Fétiche, a clump of tall trees somewhat extensively used for picnics. It has served for worse purposes, as the name shows.

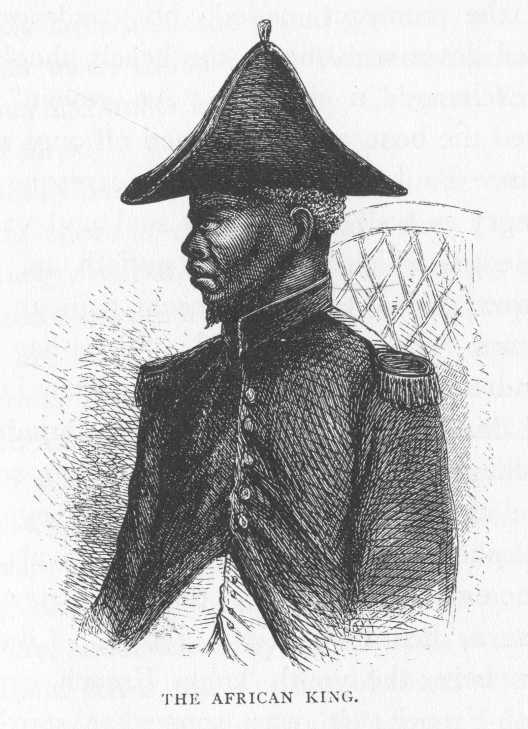

A total of two hours landed me from the Comte de Paris Roads upon the open sandy strip that supports Denistown; the single broad street runs at right angles from the river, the better to catch the sea-breeze, and most of the huts have open gables, a practice strongly to be recommended. Le Roi would not expose himself to the damp air; the consul was not so particular. His majesty’s levée took place in the verandah of a poor bamboo hut, one of the dozen which compose his capital. Seated in a chair and ready for business, he was surrounded by a crowd of courtiers, who listened attentively to every word, especially when he affected to whisper; and some pretty women collected to peep round the corners at the Utangáni (white man). 4

Mr. Wilson described Roi Denis in 1856 as a man of middle stature, with compact frame and well-made, of great muscular power, about sixty years old, very black by contrast with the snow-white beard veiling his brown face. “He has a mild and expressive eye, a gentle and persuasive voice, equally affable and dignified; and, taken altogether, he is one of the most king-like looking men I have ever met in Africa,” says the reverend gentleman. The account reminded me of Kimwere the Lion of Usumbara, drawn by Dr. Krapf. Perhaps six years had exercised a degeneratory effect upon Roi Denis, or perchance I have more realism than sentiment; my eyes could see nothing but a petit vieux vieux, nearer sixty than seventy, with a dark, wrinkled face, and an uncommonly crafty eye, one of those African organs which is always occupied in “taking your measure” not for your good.

I read out the introductory letter from Baron Didelot—the king speaks a little French and English, but of course his education ends there. After listening to my projects and to my offers of dollars, liquor, and cloth, Roi Denis replied, with due gravity, that his chasseurs were all in the plantations, but that for a somewhat increased consideration he would attach to my service his own son Ogodembe, alias Paul. It was sometime before I found out the real meaning of this crafty move; the sharp prince, sent to do me honour, intended me to recommend him to Mr. Hogg as an especially worthy recipient of “trust.” Roi Denis added an abundance of “sweet mouf,” and, the compact ended, he condescendingly walked down with me to the beach, shook hands and exchanged a civilized “Au revoir.” I reentered the boat, and we pushed off once more.

Prince Paul, a youth of the Picaresque school, a hungry as well as a thirsty soul and vain with knowledge, which we know “puffeth up,” having the true African eye on present gain as well as to future “trust,” proceeded: “Papa has at least a hundred sons,” enough to make Dan Dinmont blush, “and say” (he was not sure), “a hundred and fifty daughters. Father rules all the southern shore; the French have no power beyond the brack and there are no African rivals,”—the prince evidently thought that the new-comer had never heard of King George. Like most juniors here, the youth knew French, or rather Gaboon–French; it was somewhat startling to hear clearly and tolerably pronounced, “M’sieur, veux-tu des macacques?” But the jargon is not our S’a Leone and West-coast “English;” the superior facility of pronouncing the neo-Latin tongues became at once apparent. It is evident that European languages have been a mistake in Africa: the natives learn a smattering sufficient for business purposes and foreigners remain without the key to knowledge; hence our small progress in understanding negro human nature. Had we so acted in British India, we should probably have held the proud position which now contents us in China as in Western Africa, with factories and hulks at Bombay, Calcutta, Karachi, and Madras.

From Comte de Paris Roads the southern Gaboon shore is called in charts Le Paletuvier, the Mangrove Bank; the rhizophora is the growth of shallow brackish water, and at the projections there are fringings of reefs and “diabolitos,” dangerous to boats. After two hours we crossed the Mombe (Mombay) Creek-mouth, with its outlying rocks, and passed the fishing village of Nenga–Oga, whence supplies are sent daily to the Plateau. Then doubling a point of leek-green grass, based upon comparatively poor soil, sand, and clay, and backed by noble trees, we entered the Mbátá River, the Toutiay of the chart and the Batta Creek of M. du Chaillu’s map. It comes from the south-west, and it heads much nearer the coast than is shown on paper.

Presently the blood-red sun sank like a fire-balloon into the west, flushing with its last fierce beams the higher clouds of the eastern sky, and lighting the white and black plume of the soaring fish-eagle. This Gypohierax (Angolensis) is a very wild bird, flushed at 200 yards: I heard of, but I never saw, the Gwanyoni, which M. du Chaillu, (chapter xvi.) calls Guanionian, an eagle or a vulture said to kill deer. Rain fell at times, thunder, anything but “sweet thunder,” again rolled in the distance; and lightning flashed and forked before and behind us, becoming painfully vivid in the shades darkening apace. We could see nothing of the channel but a steel-grey streak, like a Damascus blade, in a sable sheathing of tall mangrove avenue; in places, however, tree-clumps suggested delusive hopes that we were approaching a region where man can live. On our return we found many signs of population which had escaped our sight during the fast-growing obscurity. The first two reaches were long and bulging; the next became shorter, and Prince Paul assured us that, after one to the right, and another to the left, we should fall into the direct channel. Roi Denis had promised us arrival at sunset; his son gradually protracted sunset till midnight. Still the distance grew and grew. I now learned for the first time that the boat was too large for the channel, and that oars were perfectly useless ahead.

At 8 P.M. we entered what seemed a cul de sac; it looked like charging a black wall, except where a gleam of grey light suggested the further end of the Box Tunnel, and cheered our poor hearts for a short minute, whilst in the distance we heard the tantalizing song of the wild waves. The boughs on both sides brushed the boat; we held our hands before our faces to avoid the sharp stubs threatening ugly stabs, and to fend off the low branches, ready to sweep us and our belongings into the deep swirling water. The shades closed in like the walls of the Italian’s dungeon; until our eyes grew to it, the blackness of Erebus weighed upon our spirits; perspiration poured from our brows, and in this watery mangrove-lane the pabulum vitć seemed to be wanting. After forcing a passage through three vile “gates,” the sheet-lightning announced a second tornado. We sighed for more vivid flashes, but after twenty minutes they dimmed and died away, still showing the “bush”-silhouette on either side. The tide rushed out in strength under the amphibious forest—all who know the West Coast will appreciate the position. It was impossible to advance or to remain in this devil’s den, the gig bumped at every minute, and the early flood would probably crush her against the trees. So we dropped down to the nearest “open,” which we reached at 9.30 P.M.

After enduring a third tornado we grounded, and the crew sprang ashore, saying that they were going to boil plantains on the bank. I made snug for the night with a wet waterproof and a strip of muslin, to be fastened round the mouth after the fashion of Outram’s “fever guard,” and shut my lips to save my life, by the particular advice of Dr. Catlin. The first mosquito piped his “Io Pćan” at 8 P.M.; another hour brought legions, and then began the battle for our blood. I had resolved not to sleep in the fetid air of the jungle; time, however, moved on wings of lead; a dull remembrance of a watery moon, stars dimly visible, a southerly breeze, and heavy drops falling from the trees long haunted me. About midnight, Prince Paul, who had bewailed the hardship of passing a night sans mostiquaire in the bush, and whose violent plungings showed that he failed to manage un somme, proposed to land and to fetch fire from l’habitation.

“What habitation?”

“Oh! a little village belonging to papa.”

“And why the —-didn’t you mention it?”

“Ah! this is Mponbinda, and you know we’re bound for Mbátá!”

Nothing negrotic now astonishes us, there is nought new to me in Africa. We landed upon a natural pier of rock ledge, and, after some 400 yards of good path, we entered a neat little village, and found our crew snoring snugly asleep. We “exhorted them,” refreshed the fire, and generously recruited exhausted nature with quinine, julienne and tea, potatoes and potted meats, pipes and cigars. So sped my annual unlucky day, and thus was spent my first jungle-night almost exactly under the African line.

At 5 A. M. the new morning dawned, the young tide flowed, the crabs disappeared, and the gig, before high and dry on the hard mud, once more became buoyant. Forward again! The channel was a labyrinthine ditch, an interminable complication of over-arching roots, and of fallen trees forming gateways; the threshold was a maze of slimy stumps, stems, and forks in every stage of growth and decay, dense enough to exclude the air of heaven. In parts there were ugly snags, and everywhere the turns were so puzzling, that I marvelled how a human being could attempt the passage by night. The best time for ascending is half-flood, for descending half-ebb; if the water be too high, the bush chokes the way; if too low, the craft grounds. At the Gaboon mouth the tide rises three feet; at the head of the Mbátá Creek, where it arrests the sweet water rivulet, it is, of course, higher.

And now the scene improved. The hat-palm, a brab or wild date, the spine-palm (Phœnix spinosa), and the Okumeh or cotton-tree disputed the ground with the foul Rhizophora. Then clearings appeared. At Ejéné, the second of two landing-places evidently leading to farms, we transferred ourselves to canoes, our boat being arrested by a fallen tree. Advancing a few yards, all disembarked upon trampled mud, and, ascending the bank, left the creek which supplies baths and drinking water to our destination. Striking a fair pathway, we passed westward over a low wave of ground, sandy and mouldy, and traversed a fern field surrounded by a forest of secular trees; some parasite-grown from twig to root, others blanched and scathed by the fires of heaven; these roped and corded with runners and llianas, those naked and clothed in motley patches. At 6.30 A.M., after an hour’s work, probably representing a mile, and a total of 7 h. 30 m., or six miles in a south-south-west direction from Le Plateau, we left the ugly cul de sac of a creek, and entered Mbátá, which the French call “La Plantation.”

Women and children fled in terror at our approach—and no wonder: eyes like hunted boars, haggard faces, yellow as the sails at the Cape Verdes, and beards two days long, act very unlike cosmetics. A house was cleared for us by Hotaloya, alias “Andrew,” of the Baráka Mission, the lord of the village, who, poor fellow! has only two wives; he is much ashamed of himself, but his excuse is, “I be boy now,” meaning about twenty-two. After breakfast we prepared for a sleep, but the popular excitement forbade it; the villagers had heard that a white greenhorn was coming to bag and to buy gorillas, and they resolved to make hay whilst the sun shone.

Prince Paul at once gathered together a goodly crowd of fathers and mothers, uncles and aunts, brothers and sisters, cousins and connections. A large and loud-voiced dame, “Gozeli,” swore that she was his “proper Ngwe,” being one of his numerous step mas, and she would not move without a head, or three leaves, of tobacco. Hotaloya was his brother; Mesdames Azízeh and Asúnye declared themselves his sisters, and so all. My little stock of goods began visibly to shrink, when I informed the greedy applicants that nothing beyond a leaf of tobacco and a demi verre of tafia would be given until I had seen my way to work. Presently appeared the chief huntsman appointed by Roi Denis to take charge of me, he was named Fortuna, a Spanish name corrupted to Forteune. A dash was then prepared for his majesty and for Prince Paul. I regret to say that this young nobleman ended his leave-taking by introducing a pretty woman, with very neat hands and ankles and a most mutine physiognomy, as his sister, informing me that she was also my wife pro temp. She did not seem likely to coiffer Sainte Cathérine, and here she is.

The last thing the prince did was to carry off, without a word of leave, the mission boat and the three Kru-boys, whom he kept two days. I was uneasy about these fellows, who, hating and fearing the Gaboon “bush,” are ever ready to bolt.

Forteune and Hotaloya personally knew Mpolo (Paul du Chaillu), and often spoke to me of his prowess as a chasseur and his knowledge of their tongue. But reputation as a linguist is easily made in these regions by speaking a few common sentences. The gorilla-hunter evidently had only a colloquial acquaintance with the half-dozen various idioms of the Mpongwe and Mpángwe (Fán) Bakele, Shekyani, and Cape Lopez people. Yet, despite verbal inaccuracies, his facility of talking gave him immense advantages over other whites, chiefly in this, that the natives would deem it useless to try the usual tricks upon travellers.

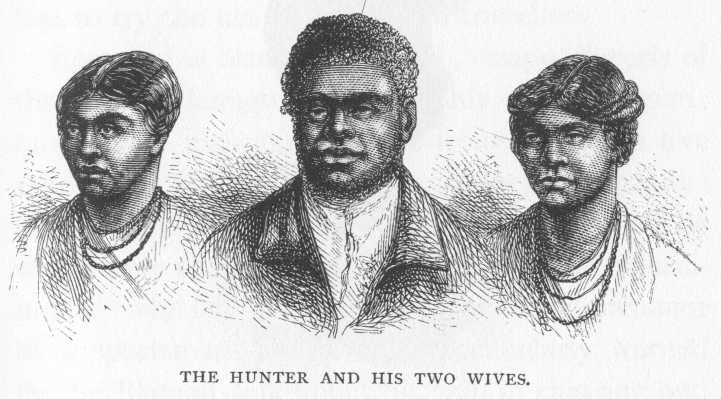

Forteune is black, short, and “trapu;” curls of the jettiest lanugo invest all his outward man; bunches of muscle stand out from his frame like the statues of Crotonian Milo; his legs are bandy; his hands and feet are large and patulous, and he wants only a hunch to make an admirable Quasimodo. He has the frank and open countenance of a sportsman—I had been particularly warned by the Plateau folk about his skill in cheating and lying. Formerly a cook at the Gaboon, he is a man of note in his tribe, as the hunter always is; he holds the position of a country gentleman, who can afford to write himself M.F.H.; he is looked upon as a man of valour; he is admired by the people, and he is adored by his wives—one of them at once took up her station upon the marital knee. Perhaps the Nimrod of Mbátá is just a little henpecked—the Mpongwe mostly are—and I soon found out that soigner les femmes is the royal road to getting on with the men. He supplies the village with “beef,” here meaning not the roast of Old England, but any meat, from a field-rat to a hippopotamus. He boasts that he has slain with his own hand upwards of a hundred gorillas and anthropoid apes, and, since the demand arose in Europe, he has supplied Mr. R.B.N. Walker and others with an average of one per month, including a live youngster; probably most, if not all, of them were killed by his “bushmen,” of whom he can command about a dozen.

Forteune began by receiving his “dash,” six fathoms of “satin cloth,” tobacco, and pipes. After inspecting my battery, he particularly approved of a smooth-bored double-barrel (Beattie of Regent Street) carrying six to the pound. Like all these people, he uses an old and rickety trade-musket, and, when lead is wanting, he loads it with a bit of tile: as many gorillas are killed with tools which would hardly bring down a wild cat, it is evident that their vital power cannot be great. He owned to preferring a charge of twenty buckshot to a single ball, and he received with joy a little fine gunpowder, which he compared complimentarily with the blasting article, half charcoal withal, to which he was accustomed.

Presently a decently dressed, white-bearded man of light complexion announced himself, with a flourish and a loud call for a chair, as Prince Koyálá, alias “Young Prince,” father to Forteune and Hotaloya and brother to Roi Denis,—here all tribesmen are of course brethren. This being equivalent to “asking for more,” it drove me to the limits of my patience. It was evidently now necessary to assume wrath, and to raise my voice to a roar.

“My hands dey be empty! I see nuffin, I hear nuffin! What for I make more dash?”

Allow me, parenthetically, to observe that the African, like the Scotch Highlander, will interpose the personal or demonstrative pronoun between noun and verb: “sun he go down,” means “the sun sets” and, as genders do not exist, you must be careful to say, “This woman he cry too much.”

The justice of my remark was owned by all; had it been the height of tyranny, the supple knaves would have agreed with me quite as politely. They only replied that “Young Prince,” being a man of years and dignity, would be dishonoured by dismissal empty-handed, and they represented him as my future host when we moved nearer the bush.

“Now lookee here. This he be bad plábbá (palaver). This he be bob! I come up for white man, you come up for black man. All white man he no be fool, ‘cos he no got black face!”

Ensued a chorus of complimentary palaver touching the infinite superiority of the Aryan over the Semite, but the point was in no wise yielded. At last Young Prince subsided into a request for a glass of rum, which being given “cut the palaver” (i.e. ended the business). I soon resolved to show my hosts, by threatening to leave them, the difference between traders and travellers. Barbot relates that the Mpongwe of olden time demanded his “dassy” before he consented to “liquor up,” and boldly asked, “If he was expected to drink gratis?” The impertinence was humoured, otherwise not an ivory would have found its way to the factory. But the traveller is not bound to endure these whimsy-whamsies; and the sooner he declares his independence the better. Many monkeys’ skins were brought to me for sale, but I refused to buy, lest the people might think it my object to make money; moreover, all were spoilt for specimens by the “points” being snipped off.

I happened during the first afternoon to show my hosts a picture of the bald-headed chimpanzee, Nchígo Mbúwwe (Troglodytes calvus), here more generally called Nchígo Mpolo, “large chimpanzee,” or Nchígo Njúe, “white-haired chimpanzee.” They recognized it at once; but when I turned over to the cottage (“Adventures,” &c., p. 423), with its neat parachute-like roof, all burst out laughing.

“You want to look him Nágo (house)?” asked Hotaloya.

“Yes, for sure,” I replied.

Forteune set out at once, carrying my gun, Selim followed me, and the rear was brought up by a couple of little prick-eared curs with a dash of the pointer, probably from St. Helena: the people will pay as much as ten dollars for a good dog. They are never used in hunting apes, as they start the game; on this occasion they nearly ran down a small antelope.

The path led through a new clearing; a field of fern and some patches of grass breaking the forest, which, almost clear of thicket and undergrowth, was a charming place for deer. The soil, thin sand overlying humus, suggested rich crops of ground-nuts; its surface was everywhere cut by nullahs, now dry, and by brooks, running crystal streams; these, when deep, are crossed by tree-trunks, the Brazilian “pingela.” After twenty minutes or so we left the “picada” (foot-path) and struck into a thin bush, till we had walked about a mile.

“Look him house, Nchígo house!” said Hotaloya, standing under a tall tree.

I saw to my surprise two heaps of dry sticks, which a schoolboy might have taken for birds’ nests; the rude beds, boughs, torn off from the tree, not gathered, were built in forks, one ten and the other twenty feet above ground, and both were canopied by the tufted tops. Every hunter consulted upon the subject ridiculed the branchy roof tied with vines, and declared that the Nchigo’s industry is confined to a place for sitting, not for shelter; that he fashions no other dwelling; that a couple generally occupies the same or some neighbouring tree, each sitting upon its own nest; that the Nchígo is not a “hermit” nor a rare, nor even a very timid animal; that it dwells, as I saw, near villages, and that its cry, “Aoo! Aoo! Aoo!” is often heard by them in the mornings and evenings. During my subsequent wanderings in Gorilla land, I often observed tall and mushroom-shaped trees standing singly, and wearing the semblance of the umbrella roof. What most puzzles me is, that M. du Chaillu (“Second Expedition,” chap, iii.) “had two of the bowers cut down and sent to the British Museum.” He adds, “They are formed at a height of twenty to thirty feet in the trees, by the animals bending over and intertwining a number of the weaker boughs, so as to form bowers, under which they can sit, protected from the rains by the masses of foliage thus entangled together, some of the boughs being so bent that they form convenient seats.” Surely M. du Chaillu must have been deceived by some vagary of nature.

The gorilla-hunter’s sketch had always reminded me of the Rev. Mr. Moffat’s account of the Hylobian Bakones, the aborigines of the Matabele country. Mr. Thompson, a missionary to Sherbro (“The Palm Land,” chap. xiii), has, however, these words:—“It is said of the chimpanzees, that they build a kind of rude house of sticks in their wild state, and fill it with leaves; and I doubt it not, for when domesticated they always want some good bed, and make it up regularly.”

Thus I come to the conclusion that the Nchígo Mpolo is a vulgar nest-building ape. The bushmen and the villagers all assured me that neither the common chimpanzee, nor the gorilla proper (Troglodytes gorilla), “make ’im house.” On the other hand, Mr. W. Winwood Reade, writing to “The Athenćum” from Loanda (Sept. 7, 1862), asserts,—“When the female is pregnant he (the gorilla) builds a nest (as do also the Kulu–Kamba and the chimpanzee), where she is delivered, and which is then abandoned.” And he thus confirms what was told to Dr. Thomas Savage (1847): “In the wild state their (i.e. the gorillas’) habits are in general like those of the Troglodytes niger, building their nests loosely in trees.”

3 Barbot, book iv. chap. 9.

4 This word is the Muzungu of the Zanzibar coast, and contracted to Utángá and even Tángá it is found useful in expressing foreign wares; Utangáni’s devil-fire, for instance, is a lucifer match.