THE ROMANCE OF

ISABEL LADY BURTON

THE STORY OF HER LIFE

TOLD IN PART BY HERSELF

AND IN PART BY

W H WILKINS

WITH PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

eBooks@Adelaide

2006

Originally published by Dodd Mead & Company in 1897

This web edition published by eBooks@Adelaide.

Rendered into HTML by Steve

Thomas.

Last updated Sunday March 19 2006.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence

(available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.1/au/).

You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work,

and to make derivative works under the following conditions: you

must attribute the work in the manner specified by the licensor;

you may not use this work for commercial purposes; if you alter,

transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the

resulting work only under a license identical to this one. For any

reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license

terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you

get permission from the licensor. Your fair use and other rights

are in no way affected by the above.

For offline reading, the complete set of pages is available for

download from

http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/b/burton/isabel/romance/romance.zip

The complete work is also available as a single file, at

http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/b/burton/isabel/romance/complete.html

A MARC21 Catalogue record for this edition can be downloaded

from http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/b/burton/isabel/romance/marc.bib

eBooks@Adelaide

The University of Adelaide Library

University of Adelaide

South Australia 5005

Note to this Edition

In creating this web edition, no attempt has been made to retain

"stylistic" layout features of the work on which it is based.

Layout styles which are irrelevant to the meaning of the work have been changed

to our "house" style.

Content changes have been restricted to the following :

- Footnotes and/or End-notes have been relocated as chapter end-notes, and renumbered.

- Numbering of footnotes is sequential and continuous through the entire work.

- Illustrations have been relocated to the nearest paragraph start or end.

List of Illustrations

- Original Title Page to Volume

I

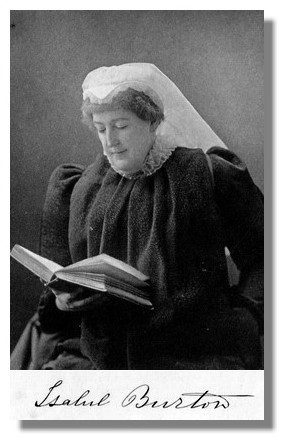

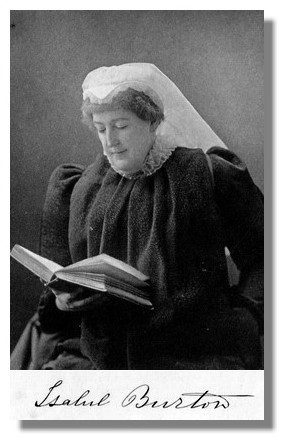

- Lady Burton at the age of

17

- Wardour Castle

- Lineage of Lady Burton

- New Hall, Chelmsford

- Richard Burton in 1848 in Native

Dress

- The Ramparts, Boulogne

- Burton On His Pilgrimage to

Mecca

- Venice

- Lady Burton at the Time of Her

Marriage

- The Bay of Funchal, Madeira

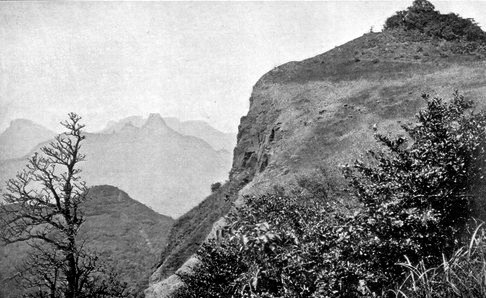

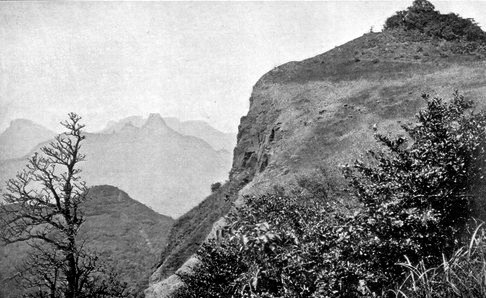

- The Peak of Teneriffe, From the Vale

of Orotava

- Santos

- Petropolis

- Sao Paulo

- The Bay of Rio

- The Slave Muster at Morro

Velho

- Frontispiece to Volume II

- Lady Burton in 1869

- The Boulevart, Alexandria

- Damascus, From the Desert

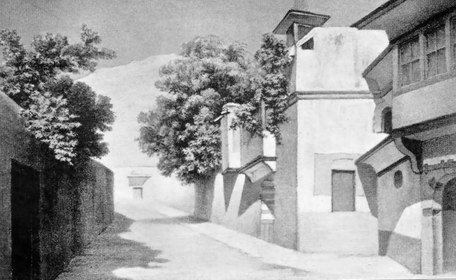

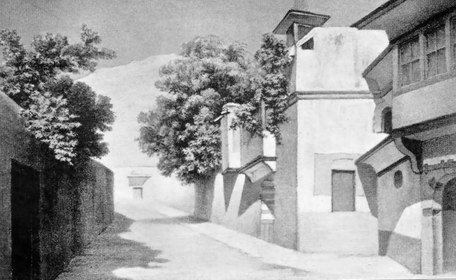

- The Burtons' House Salahíyyeh,

Damascus. From a sketch by the late Lord Leighton

- The Court of the Great Mosque,

Damascus.

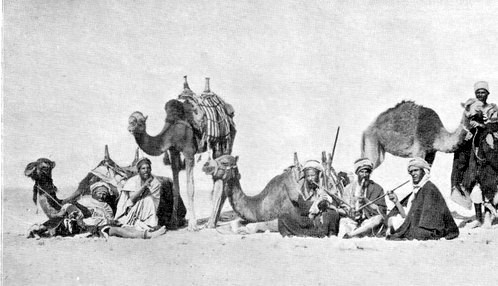

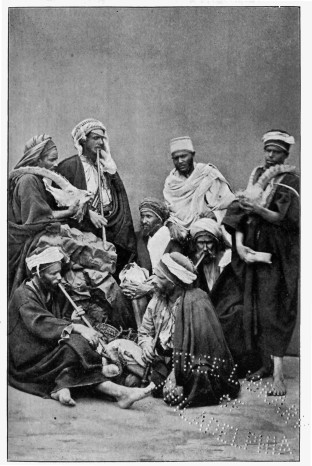

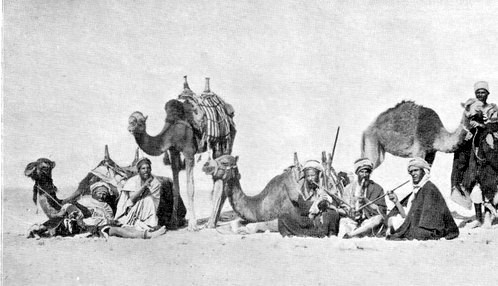

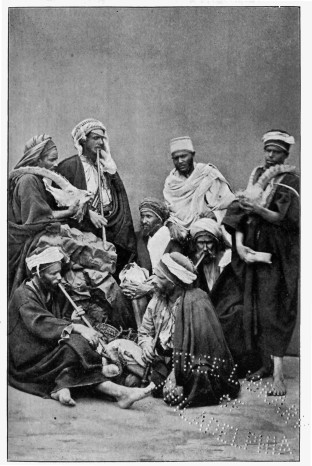

- Arab Camel-Drivers.

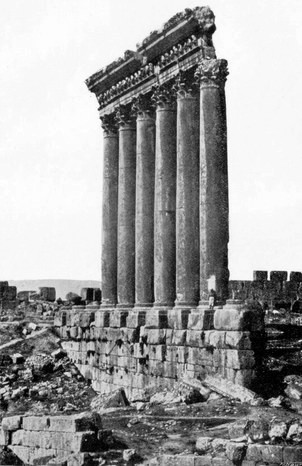

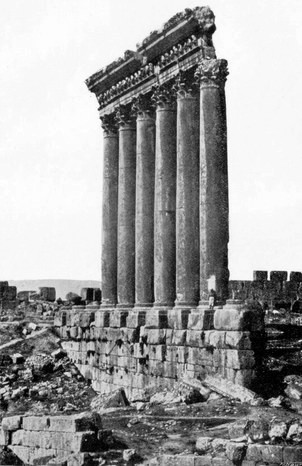

- Ba'albak.

- “The Moon,” Lady Burton's

Syrian Maid

- Mosque of Omar, Jerusalem.

- The Dead Sea.

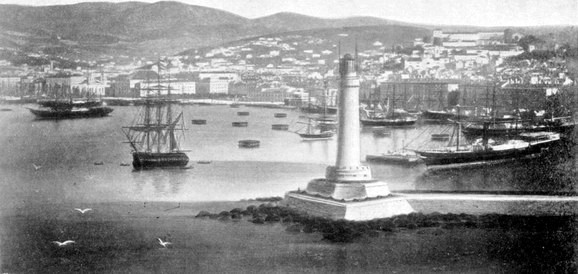

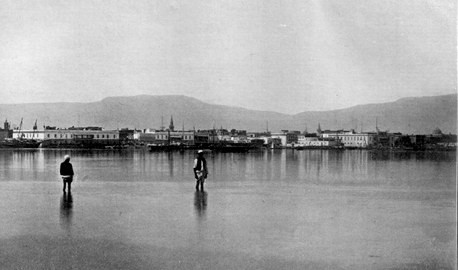

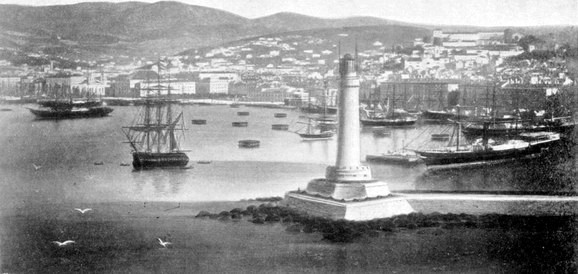

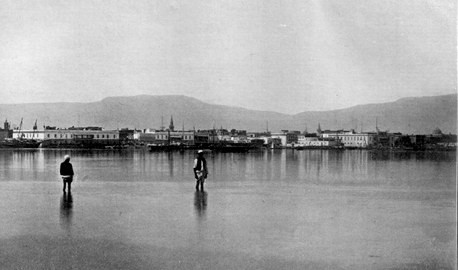

- Trieste.

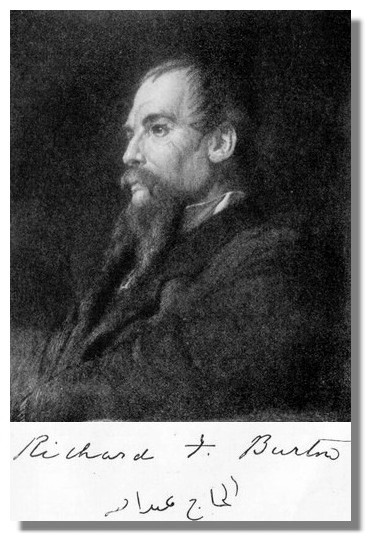

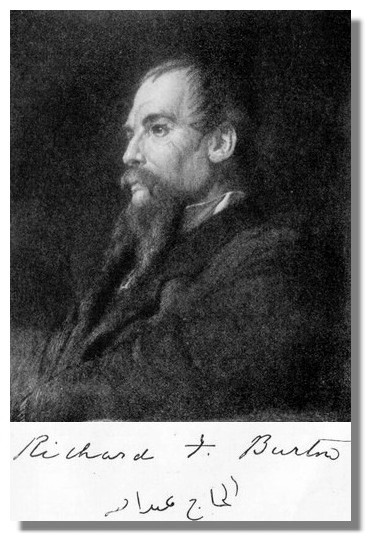

- From the portrait by the late Lord

Leighton.

- Port Said.

- Arab Camel-Drivers.

- The Caves of Elephanta.

- Panorama Point and the Bhao Madin

Hills, Mátherán.

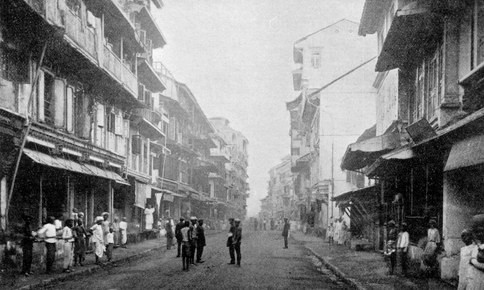

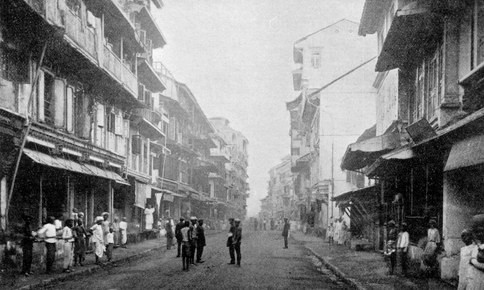

- The Borah (Native) Bazar,

Bombay.

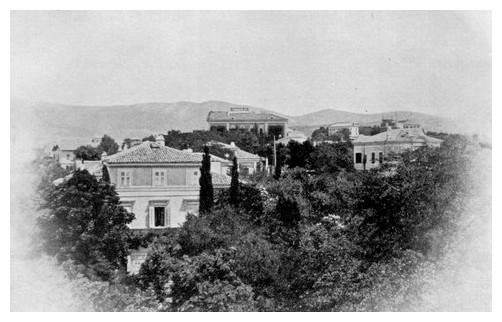

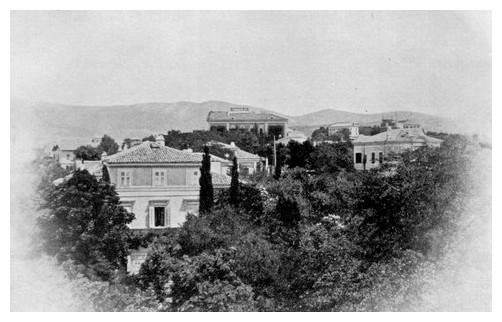

- Goa.

- Suez.

- The Burtons' House at

Trieste.

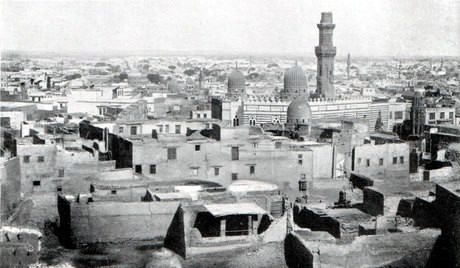

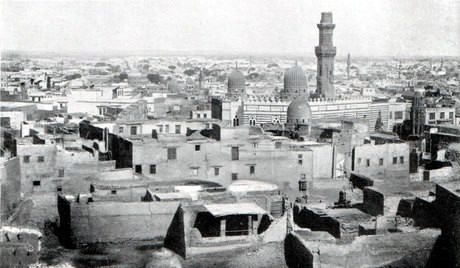

- Cairo.

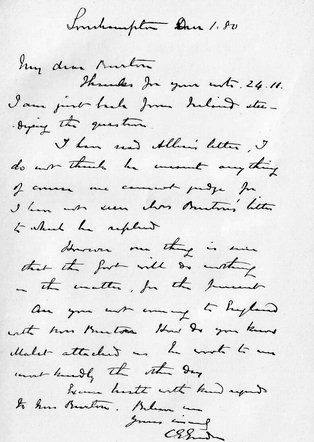

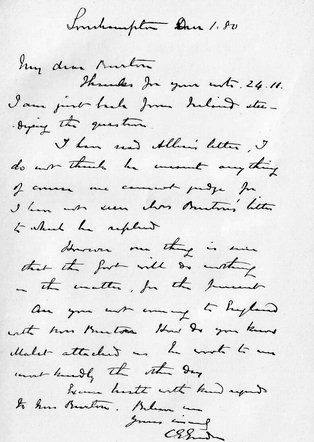

- Autograph Letter of General

Gordon.

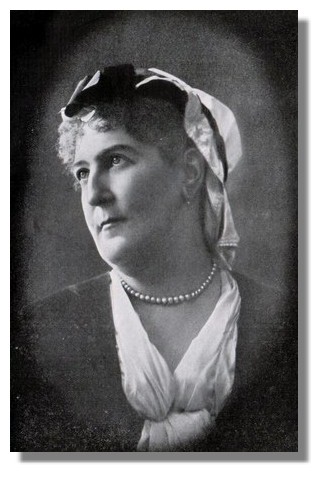

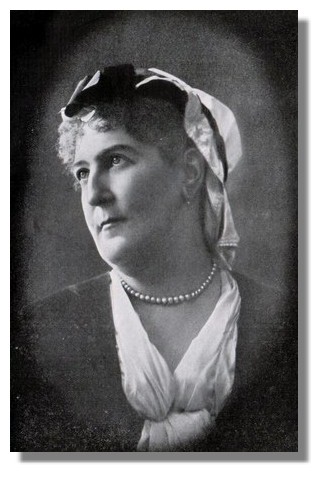

- Lady Burton in 1887.

- A Native Lady, Tunis.

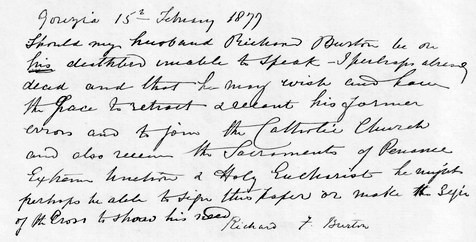

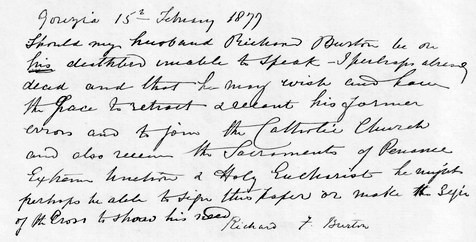

- Facsimile of Declaration by Sir

Richard Burton

- The Room in Which Lady Burton

Died

- The Arab Tent at Mortlake

Original Title Page

Lady Burton at the age of 17

From an unfinished drawing

To

Her Sister

Mrs. Gerald Fitzgerald

I Dedicate This Book

Preface

Lady Burton began her autobiography a few months before she

died, but in consequence of rapidly failing health she made little

progress with it. After her death, which occurred in the spring of

last year, it seemed good to her sister and executrix, Mrs.

Fitzgerald, to entrust the unfinished manuscript to me, together

with sundry papers and letters, with a view to my compiling the

biography. Mrs. Fitzgerald wished me to undertake this work, as I

had the good fortune to be a friend of the late Lady Burton, and

one with whom she frequently discussed literary matters; we were,

in fact, thinking of writing a romance together, but her illness

prevented us.

The task of compiling this book has not been an easy one, mainly

for two reasons. In the first place, though Lady Burton published

comparatively little, she was a

voluminous writer, and she left behind her such a mass of letters

and manuscripts that the sorting of them alone was a formidable

task. The difficulty has been to keep the book with limits. In the

second place, Lady Burton has written the Life of her husband; and

though in that book she studiously avoided putting herself forward,

and gave to him all the honour and the glory, her life was so

absolutely bound up with his, that of necessity she covered some of

the ground which I have had to go over again, though not from the

same point of view. So much has been written concerning Sir Richard

Burton that it is not necessary for me to tell again the story of

his life here, and I have therefore been able to write wholly of

his wife, an equally congenial task. Lady Burton was as remarkable

as a woman as her husband was as a man. Her personality was as

picturesque, her individuality is unique, and, allowing for her

sex, her life was as full and varied as his.

It has been my aim, wherever possible, throughout this book to

let Lady Burton tell the story of her life in her own words, and

keep my narrative in the background. To this end I have revised and

incorporated the fragment of autobiography which was cut short by her death, and I have also pieced

together all her letters, manuscripts, and journals which have a

bearing on her travels and adventures. I have striven to give a

faithful portrait of her as revealed by herself. In what I have

succeeded, the credit is hers alone: in what I have failed, the

fault is mine, for no biographer could have wished for a more

eloquent subject than this interesting and fascinating woman. Thus,

however imperfectly I may have done my share of the work, it

remains the record of a good and noble life — a life lifted up,

a life unique in its self-sacrifice and devotion.

Last December, when this book was almost completed, a volume was

published calling itself The True Life of Captain Sir Richard

F. Burton, written by his niece, Miss Georgiana M. Stisted,

stated to be issued “with the authority and approval of the

Burton family.” This statement is not correct — at any

rate not wholly so; for several of the relatives of the late Sir

Richard Burton have written to Lady Burton’s sister to say

that they altogether disapprove of it. The book contained a number

of cruel and unjust charges against Lady Burton, which were

rendered worse by the fact that they were not made until she was

dead and could no longer defend herself. Some of these attacks were

so paltry and malevolent, and so utterly

foreign to Lady Burton’s generous and truthful character,

that they may be dismissed with contempt. The many friends who knew

and loved her have not credited them for one moment, and the animus

with which they were written is so obvious that they have carried

little weight with the general public. But three specific charges

call for particular refutation, as silence on them might be

misunderstood. I refer to the statements that Lady Burton was the

cause of her husband’s recall from Damascus; that she acted

in bad faith in the matter of his conversion to the Roman Catholic

Church; and to the impugning of the motives which led her to burn

The Scented Garden. I should like to emphasize the fact

that none of these controversial questions formed part of the

original scheme of this book, and they would not have been alluded

to had it not been for Miss Stisted’s unprovoked attack upon

Lady Burton’s memory. It is only with reluctance, and solely

in a defensive spirit, that they are touched upon now. Even so, I

have suppressed a good deal, for there is no desire on the part of

Lady Burton’s relatives or myself to justify her at the

expense of the husband whom she loved, and who loved her. But in

vindicating her it has been necessary to tell the truth. If

therefore, in defending Lady Burton against

these accusations, certain facts have come to light which would

otherwise have been left in darkness, those who have wantonly

attacked the dead have only themselves to blame.

In conclusion, I should like to acknowledge my indebtedness to

those who have kindly helped me to make this book as complete as

possible. I am especially grateful to Mrs. Fitzgerald for much

encouragement and valuable help, including her reading of the

proofs as they went through the press, so that the book may be

truly described as an authorized biography. I also wish to thank

Miss Plowman, the late Lady Burton’s secretary, who has been

of assistance in many ways. I acknowledge with gratitude the

permission of Captain L. H. Gordon to publish certain letters which

the late General Gordon wrote to Sir Richard and Lady Burton, and

the assistance which General Gordon’s niece, Miss Dunlop,

kindly gave me in this matter. My thanks are likewise due to the

Executors of the late Lord Leighton for permission to publish Lord

Leighton’s portrait of Sir Richard Burton; to Lady Thornton

and others for many illustrations; and to Lady Salisbury, Lady

Guendolen Ramsden, Lord Llandaff, Sir Henry Elliot, Mr. W. F. D. Smith, Baroness Paul de Ralli, Miss

Bishop, Miss Alice Bird, Madame de Gutmansthal-Benvenuti, and

others, for permission to publish sundry letters in this book.

W. H. WILKINS.

8, Mandeville Place, W.,

April, 1897.

Book I

Waiting

(1831-1861)

I have known love and yearning from the years

Since mother-milk I drank, nor e’er was free.

Alf Laylah wa Laylah

(Burton’s “Arabian Nights”).

Chapter I

Birth and Lineage

Man is known among men as his deeds attest,

Which make noble origin manifest.

Alf Laylah wa Laylah

(Burton’s “Arabian Nights”).

Isabel, Lady Burton, was by birth an Arundell of Wardour, a

daughter of one of the oldest and proudest houses of England. The

Arundells of Wardour are a branch of the great family of whom it

was sung:

Ere William fought and Harold fell

There were Earls of Arundell.

The Earls of Arundell before the Conquest are somewhat lost in

the mists of antiquity, and they do not affect the branch of the

family from which Lady Burton sprang. This branch traces its

descent in a straight line from one Roger de Arundell, who,

according to Domesday, had estates in Dorset and Somerset,

and was possessed of twenty-eight lordships. The Knights of

Arundell were an adventurous race. One of the most famous was Sir

John Arundell, a valiant commander who

served Henry VI. in France. The grandson of this doughty knight,

also Sir John Arundell, was made a Knight Banneret by Henry VII.

for his valour at the sieges of Tiroven and Tournay, and the battle

that ensued. At his death his large estates were divided between

the two sons whom he had by his first wife, the Lady Eleanor Grey,

daughter of the Marquis of Dorset, whose half-sister was the wife

of Henry VII. The second son, Sir Thomas Arundell, was given

Wardour Castle in Wiltshire, and became the ancestor of the

Arundells of Wardour.

The House of Wardour was therefore founded by Sir Thomas

Arundell, who was born in 1500. He had the good fortune in early

life to become the pupil, and ultimately to win the friendship, of

Cardinal Wolsey. He played a considerable part throughout the

troublous times which followed on the King’s quarrel with the

Pope, and attained great wealth and influence. He was a

cousin-german of Henry VIII., and he was allied to two of

Henry’s ill-fated queens through his marriage with Margaret,

daughter of Lord Edmond Howard, son of Thomas, Duke of Norfolk. His

wife was a cousin-german of Anne Boleyn and a sister of Catherine

Howard. Sir Thomas Arundell was a man of intellectual powers and

administrative ability. He became Chancellor to Queen Catherine

Howard, and he stood high in the favour of Henry VIII. But in the

following reign evil days came upon him. He was accused of

conspiring with the Lord Protector Somerset to kill the Earl of

Northumberland, a charge utterly false, the

real reason of his impeachment being that Sir Thomas had been chief

adviser to the Duke of Somerset and had identified himself with his

policy. He was beheaded on Tower Hill a few days after the

execution of the Duke of Somerset. Thus died the founder of the

House of Wardour.

In Sir Thomas Arundell’s grandson, who afterwards became

first Lord Arundell of Wardour, the adventurous spirit of the

Arundells broke forth afresh. When a young man, Thomas Arundell,

commonly called “The Valiant,” went over to Germany,

and served as a volunteer in the Imperial army in Hungary. He

fought against the Turks, and in an engagement at Grau took their

standard with his own hands. On this account Rudolph II., Emperor

of Germany, created him Count of the Holy Roman Empire, and decreed

that “every of his children and their descendants for ever,

of both sexes, should enjoy that title.” So runs the wording of the

charter.1 On Sir Thomas

Arundell’s return to England a warm dispute arose among the

Peers whether such a dignity, so conferred by a foreign potentate,

should be allowed place or privilege in England. The matter was

referred to Queen Elizabeth, who answered,

“that there was a close tie of affection between the Prince

and subject, and that as chaste wives should have no glances but

for their own spouses, so should faithful subjects keep their eyes

at home and not gaze upon foreign crowns; that we for our part do

not care that our sheep should wear a stranger’s marks, nor

dance after the whistle of every foreigner.” Yet it was she

who sent Sir Thomas Arundell in the first instance to the Emperor

Rudolph with a letter of introduction, in which she spoke of him as

her “dearest cousin,” and stated that the descent of

the family of Arundell was derived from the blood royal. James I.,

while following in the footsteps of Queen Elizabeth, and refusing

to acknowledge the title conferred by the Emperor, acknowledged Sir

Thomas Arundell’s worth by creating him a Baron of England

under the title of Baron Arundell of Wardour. It is worthy of note

that James II. recognized the right of the title of Count of the

Holy Roman Empire to Lord Arundell and all his descendants of both

sexes in a document of general interest to Catholic families.

Wardour Castle

Thomas, second Baron Arundell of Wardour, married Blanche,

daughter of the Earl of Worcester. This Lady Arundell calls for

special notice, as she was in many ways the prototype of her lineal

descendant, Isabel. When her husband was away serving with the

King’s army in the Great Rebellion, Lady Arundell bravely

defended Wardour for nine days, with only a handful of men, against

the Parliamentary forces who besieged it. Lady Arundell then

delivered up the castle on honourable terms,

which the besiegers broke when they took possession. They were,

however, soon dislodged by Lord Arundell, who, on his return,

ordered a mine to be sprung under his castle, and thus sacrificed

the ancient and stately pile to his loyalty. He and his wife then

turned their backs on their ruined home, and followed the

King’s fortunes, she sharing with uncomplaining love all her

husband’s trials and privations. Lord Arundell, like the rest

of the Catholic nobility of England, was a devoted Royalist. He

raised at his own expense a regiment of horse for the service of

Charles I., and in the battle of Lansdowne, when fighting for the

King, he was shot in the thigh by a brace of pistol bullets,

whereof he died in his Majesty’s garrison at Oxford. He was

buried with great pomp in the family vault at Tisbury. His devoted

wife, like her descendant Lady Burton, that other devoted wife who

strongly resembled her, survived her husband barely six years. She

died at Winchester; but she was buried by his side at Tisbury,

where her monument may still be seen.

Henry, third Lord Arundell, succeeded his father in his titles

and honours. Like many who had made great sacrifices to the Royal

cause, he did not find an exceeding great reward when the King came

into his own again. As Arundell of Wardour was one of the strictest

and most loyal of the Catholic families of England, its head was

marked out for Puritan persecution. In 1678 Lord Arundell was, with

four other Catholic lords, committed a prisoner to the Tower,

upon the information of the infamous Titus

Oates and other miscreants who invented the “Popish

Plots.” Lord Arundell was confined in the Tower until 1683,

when he was admitted to bail. Five years’ imprisonment for no

offence save fidelity to his religion and loyalty to his king was

cruel injustice; but in those days, when the blood of the best

Catholic families in England ran like water on Tower Hill, Lord

Arundell was lucky to have escaped with his head. On James

II.‘s accession to the throne he was sworn of the Privy

Council and held high office. On King James’s abdication he

retired to his country seat, where he lived in great style and with

lavish hospitality. Among other things he kept a celebrated pack of

hounds, which afterwards went to Lord Castlehaven, and thence were

sold to Hugo Meynell, and became the progenitors of the famous

Quorn pack.

Henry, the sixth Baron, is noteworthy as being the last Lord

Arundell of Wardour from whom Isabel was directly descended (see p.

9), and with him our immediate interest in the Arundells of Wardour

ceases. Lady Burton was the great-granddaughter of James Everard

Arundell, his third and youngest son. Her father, Mr. Henry Raymond

Arundell, was twice married. His first wife died within a year of

their marriage, leaving one son. Two years later, in 1830, Mr.

Henry Arundell married Miss Eliza Gerard, a sister of Sir Robert

Gerard of Garswood, who was afterwards created Lord Gerard. The

following year, 1831, Isabel, the subject of this memoir, was

born.

[click to enlarge]

I have dwelt on Lady Burton's lineage for several reasons. In the first place,

she herself would have wished it. She paid great attention to her

pedigree, and at one time contemplated writing a book on the

Arundells of Wardour, and with this view collected a mass of

information, which, with characteristic generosity, she afterwards

placed at Mr. Yeatman’s disposal for his History of the

House of Arundell. She regarded her forefathers with

reverence, and herself as their product. But proud though she was

of her ancestry, there never was a woman freer from the vulgarity

of thrusting it forward upon all and sundry, or of expecting to be

honoured for it alone. Though of noble descent, not only on her

father’s side, but on her mother’s as well (for the

Gerards are a family of eminence and antiquity, springing from the

common ancestor of the Dukes of Leinster in Ireland and the Earls

of Plymouth, now extinct, in England), yet she counted it as

nothing compared with the nobility of the inner worth, the majesty

which clothes the man, be he peasant or prince, with righteousness.

She often said, “The man only is noble who does noble

deeds,” and she always held that

He, who to ancient wreaths can bring no more

From his own worth, dies bankrupt on the score.

Another reason why I have called attention to Lady

Burton’s ancestry is because she attached considerable

importance to the question of heredity generally, quite apart from

any personal aspect. She looked upon it as a field in which Nature

ever reproduces herself, not only with regard to the physical

organism, but also the psychical qualities.

But with it all she was no pessimist, for she believed that there

was in every man an ever rallying force against the inherited

tendencies to vice and sin. She was always “on the side of

the angels.”

I remember her once saying: “Since I leave none to come

after me, I must needs strive to be worthy of those who have gone

before me.”

And she was worthy — she, the daughter of an ancient race,

which seems to have found in her its crowning consummation and

expression. If one were fanciful, one could see in her many-sided

character, reflected as in the facets of a diamond, the great

qualities which had been conspicuous in her ancestors. One could

see in her, plainly portrayed, the roving, adventurous spirit which

characterized the doughty Knights of Arundell in days when the

field of travel and adventure was much more limited than now. One

could mark the intellectual and administrative abilities, and

perhaps the spice of worldly wisdom, which were conspicuous in the

founder of the House of Wardour. One could note in her the

qualities of bravery, dare-devilry, and love of conflict which

shone out so strongly in the old Knight of Arundell who raised the

sieges of Tiroven and Tournay, and in “The Valiant” who

captured with his own hands the banner of the infidel. One could

see the reflex of that loyalty to the throne which marked the Lord

Arundell who died fighting for his king. One could trace in her the

same tenacity and devotion with which all her race has clung to the

ancient faith and which sent one of them to the Tower. Above all

one could trace her likeness to Blanche Lady Arundell, who held Wardour at her lord’s bidding against

the rebels. She was like her in her lion-hearted bravery, in her

proud but generous spirit, in her determination and resource, and

above all in her passionate wifely devotion to the man to whom she

felt herself “destined from the beginning.”

In sooth they were a goodly company, these Arundells of Wardour,

and ’tis such as they, brave men and good women in every rank

of life, who have made England the nation she is to-day. Yet of

them all there was none nobler, none truer, none more remarkable

than this late flower of their race, Isabel Burton.

Chapter II2

My Childhood and Youth

(1831-1849)

As star knows star across the ethereal sea,

So soul feels soul to all eternity.

Blessed be they who invented pens, ink, and paper!

I have heard men speak with infinite contempt of authoresses. As

a girl I did not ask my poor little brains whether this mental

attitude towards women was generous in the superior animal or not;

but I did like to slope off to my own snug little den, away from my

numerous family, and scribble down the events of my ordinary,

insignificant, uninteresting life, and write about my little

sorrows, pleasures, and peccadilloes. I was only one of the

“wise virgins,” providing for the day when I should be

old, blind, wrinkled, forgetful, and miserable, and might like such

a record to refresh my failing memory. So I went back, by way of

novelty, beyond my memory, and gleaned details from my father.

For those who like horoscopes, I was born on a Sunday at ten

minutes to 9 a.m., March 20, 1831, at 4, Great Cumberland Place,

near the Marble Arch. I am not able to give the aspect of the

planets on this occasion; but, unlike most babes, I was born with

my eyes open, whereupon my father predicted that I should be very

“wide awake.” As soon as I could begin to move about

and play, I had such a way of pointing my nose at things, and of

cocking my ears like a kitten, that I was called

“Puss,” and shall probably be called Puss when I am

eighty. I was christened Isabel, after my father’s first

wife, née Clifford, one of his cousins. She died, after a

short spell of happiness, leaving him with one little boy, who at

the time I was born was between three and four years old.

It is a curious fact that my mother, Elizabeth Gerard, and

Isabel Clifford, my father’s first wife, were bosom friends,

school-fellows, and friends out in the world together; and amongst

other girlish confidences they used to talk to one another about

the sort of man each would marry. Both their men were to be tall,

dark, and majestic; one was to be a literary man, and a man of

artistic tastes and life; the other was to be a statesman. When

Isabel Clifford married my father, Henry Raymond Arundell (of

Wardour), her cousin, my mother, seeing he was a small, fair,

boyish-looking man, whose chief hobbies were hunting and shooting,

said, “I am ashamed of you, Isabel! How can you?”

Nevertheless she used to go and help her to make her baby-clothes

for the coming boy. After Isabel’s death nobody, except my

father, deplored her so much as her dear

friend my mother; so that my father only found consolation (for he

would not go out nor meet anybody in the intensity of his grief) in

talking to my mother of his lost wife. From sympathy came pity,

from pity grew love, and three years after Isabel’s death my

mother and my father were married. They had eleven children, great

and small; I mean that some only lived to be baptized and died,

some lived a few years, and some grew up. 3

To continue my own small life, I can remember distinctly

everything that has happened to me from the age of three. I do not

know whether I was pretty or not; there is a very sweet miniature

of me with golden hair and large blue eyes, and clad in a white

muslin frock and gathering flowers, painted by one of the best

miniature painters of 1836, when miniatures were in vogue and

photographs unknown. My mother said I was “lovely,” and

my father said I was “all there”; but I am told my

uncles and aunts used to put my mother in a rage by telling her how

ugly I was. My father adored me, and spoilt me absurdly; he

considered me an original, a bit of “perfect nature.”

My mother was equally fond of me, but severe — all her

spoiling, on principle, went to her step-son, whose name was

Theodore.

When my father and mother were first married, James Everard

Arundell, my father’s first cousin, and my godfather, was the

then Lord Arundell of Wardour. He was reputed to be the handsomest

peer of the day, and he was married to a sister of the Duke of

Buckingham. He invited my father and

mother, as the two wives were friends, to come and occupy one wing

of Wardour immediately after their marriage, and they did so. When

James Everard died, my parents left Wardour, and took a house in

Montagu Place at the top of Bryanston Square, and passed their

winters hunting at Leamington.

We children were always our parents’ first care. Great

attention was paid to our health, to our walks, to our dress, our

baths, and our persons; our food was good, but of the plainest; we

had a head nurse and three nursery-maids; and, unlike the present,

everything was upstairs — day nurseries and night nurseries and

schoolroom. The only times we were allowed downstairs were at two

o’clock luncheon (our dinner), and to dessert for about a

quarter of an hour if our parents were dining alone or had very

intimate friends. On these occasions I was dressed in white muslin

and blue ribbons, and Theodore, my step-brother, in green velvet

with turn-over lace collar after the fashion of that time. We were

not allowed to speak unless spoken to; we were not allowed to ask

for anything unless it was given to us. We kissed our

father’s and mother’s hands, and asked their blessing

before going upstairs, and we stood upright by the side of them all

the time we were in the room. In those days there was no lolling

about, no Tommy-keep-your-fingers-out-of-the-jam, no

Dick-crawling-under-the-table-pinching-people’s-legs as

nowadays. We children were little gentlemen and ladies, and people

of the world from our birth; it was the old

school. The only diversion from this strict rule was an occasional

drive in the park with mother, in a dark green chariot with

hammer-cloth, and green and gold liveries and powdered wigs for

coachman and footman: no one went into the park in those days

otherwise. My daily heart-twinges were saying good-night to my

mother, always with an impression that I might not see her again,

and the other terror was the old-fashioned rushlight shade, like a

huge cylinder with holes in it, which made hideous shadows on the

bedroom walls, and used to frighten me horribly every time I woke.

The most solemn thing to me was the old-fashioned Charley, or

watchman, pacing up and down the street, and singing in deep and

mournful tone, “Past one o’clock, and a cloudy

morning.”

At the age of ten I was sent to the Convent of the Canonesses of

the Holy Sepulchre, New Hall, Chelmsford, and left there when I was

sixteen. In one sense my leaving school so early was a misfortune;

I was just at the age when one begins to understand and love

one’s studies. I ought to have been kept at the convent, or

sent to some foreign school; but both my father and mother wanted

to have me at home with them.

I want to describe my home of that period. It was called Furze

Hall, near Ingatestone, Essex. Dear place! I can shut my eyes and

see it now. It was a white, straggling, old-fashioned,

half-cottage, half-farmhouse, built by bits, about a hundred yards

from the road, from which it was completely hidden by trees. It was

buried in bushes, ivy, and flowers. Creepers covered the walls and the verandahs, and crawled in

at the windows, making the house look like a nest; it was

surrounded by a pretty flower garden and shrubberies, and the

pasture-land had the appearance of a small park. There were stables

and kennels. Behind the house a few woods and fields, perhaps fifty

acres, and a little bit of water, all enclosed by a ring fence,

comprised our domain. Inside the house the hall had the appearance

of the main cabin of a man-of-war, and opened all around into rooms

by various doors: one into a small library, which led to a pretty,

cheerful little drawing-room, with two large windows down to the

ground; one opened on to a trim lawn, the other into a

conservatory; another door opened into a smoking-room, for the male

part of the establishment, and the opposite one into a little

chapel; and a dining-room, running off by the back door with glass

windows to the ground, led to the garden. There was a pretty

honeysuckle and jessamine porch, which rose just under my window,

in which wrens and robins built their nests, and birds and bees

used to pay me a visit on summer evenings. We had many shady walks,

arbours, bowers, a splendid slanting laurel hedge, and a beautiful

bed of dahlias, all colours and shades. A beech-walk like the aisle

of a church had a favourite summer-house at the end. The pretty

lawn was filled, as well as the greenhouse, with the choicest

flowers; and we had rich crops of grapes, the best I ever knew. I

remember a mulberry tree, under the shade of which was a grave and

tombstone and epitaph, the remains and memorial of a faithful old

dog; and I remember a pretty pink may tree,

a large white rose, and an old oak, with a seat round it. Essex is

generally flat; but around us it was undulating and well-wooded,

and the lanes and drives and rides were beautiful. We were rather

in a valley, and a pretty road wound up a rise, at the top of which

our tall white chimneys could be seen smoking through the trees.

The place could boast no grandeur; but it was my home, I passed my

childhood there, and loved it.

New Hall, Chelmsford

We used to have great fun on a large bit of water in the park of

one of our neighbours, — in the ice days in winter with

sledges, skating, and sliding; in the summer-time we used to

scamper all over the country with long poles and jump over the

hedges. Nevertheless, I had a great deal of solitude, and I passed

much time in the woods reading and contemplating. Disraeli’s

Tancred and similar occult books were my favourites; but

Tancred, with its glamour of the East, was the chief of

them, and I used to think out after a fashion my future life, and

try to solve great problems. I was forming my character.

And as I was as a child, so I am now. I love solitude. I have

met with people who dare not pass a moment alone; many seem to

dread themselves. I find no greater happiness than to be alone out

of doors, either on the sea-beach or in a wood, and there reflect.

With me solitude is a necessary consolation; I can soothe my

miseries, enjoy my pleasures, form my mind, reconcile myself to

disappointments, and plan my conduct. A person may be sorrowful

without being alone, and the mind may be

alone in a large assembly, in a crowded city, but not so

pleasantly. I have heard that captives can solace themselves by

perpetually thinking of what they loved best; but there is a danger

in excess of solitude, lest our thoughts run the wrong way and

ferment into eccentricity. Every right-minded person must think,

and thought comes only in solitude. He must ponder upon what he is,

what he has been, what he may become. The energies of the soul rise

from the veiled obscurity it is placed in during its contact with

the world. It is when alone that we obtain cheerful calmness and

content, and prepare for the hour of action. Alone, we acquire a

true notion of things, bear the misfortunes of life calmly, look

firmly on the pride and insolence of the great, and dare to think

for ourselves, which the majority of the great dare not. When can

the soul feel that it lives, and is great, free, noble, immortal,

if not in thought? Oh! one can learn in solitude what the worldly

have no idea of. True it is that some souls capable of reflection

plunge themselves into an endless abyss, and know not where to

stop. I have never felt one of those wild, joyous moments when we

brood over our coming bliss, and create a thousand glorious

consequences. But I have known enough of sorrow to appreciate

rightly any moment without an immediate care. There are moments of

deep feeling, when one must be alone in self-communion, alike to

encounter good fortune or danger and despair, even if one draws out

the essence of every misery in thought.

I was enthusiastic about gypsies, Bedawin Arabs, and everything

Eastern and mystic, and especially about a wild and lawless life.

Very often, instead of going to the woods, I used to go down a

certain green lane; and if there were any oriental gypsies there, I

would go into their camp and sit for an hour or two with them. I

was strictly forbidden to associate with them in our lanes, but it

was my delight. When they were only travelling tinkers or

basket-menders, I was very obedient; but wild horses would not have

kept me out of the camps of the oriental, yet English-named, tribes

of Burton, Cooper, Stanley, Osbaldiston, and one other tribe whose

name I forget. My particular friend was Hagar Burton, a tall,

slender, handsome, distinguished, refined woman, who had much

influence in her tribe. Many an hour did I pass with her (she used

to call me “Daisy”), and many a little service I did

them when any of her tribe were sick, or got into a scrape with the

squires anent poultry, eggs, or other things. The last day I saw

Hagar Burton in her camp she cast my horoscope and wrote it in

Romany. The rest of the tribe presented me with a straw fly-catcher

of many colours, which I still have. The horoscope was translated

to me by Hagar. The most important part of it was this:

“You will cross the sea, and be in the same town with your

Destiny and know it not. Every obstacle will rise up against you,

and such a combination of circumstances, that it will require all

your courage, energy, and intelligence to meet them. Your life will

be like one swimming against big waves; but

God will be with you, so you will always win. You will fix your eye

on your polar star, and you will go for that without looking right

or left. You will bear the name of our tribe, and be right proud of

it. You will be as we are, but far greater than we. Your life is

all wandering, change, and adventure. One soul in two bodies in

life or death, never long apart. Show this to the man you take for

your husband. — Hagar Burton.”

She also prophesied:

“You shall have plenty to choose from, and wait for years;

but you are destined to him from the beginning. The name of our

tribe shall cause you many a sorrowful, humiliating hour; but when

the rest who sought him in the heyday of his youth and strength

fade from his sight, you shall remain bright and purified to him as

the morning star, which hangs like a diamond drop over the sea.

Remember that your destiny for your constancy will triumph, the

name we have given you will be yours, and the day will come when

you will pray for it, and be proud of it.”

Much other talk I had with Hagar Burton sitting around the

camp-fire, and then she went from me; and I saw her but once again,

and that after many years.

This was the ugliest time of my life. Every girl has an ugly

age. I was tall, plump, and meant to be fair, but was always tanned

and sunburnt. I knew my good points. What girl does not? I had

large, dark blue, earnest eyes, and long, black eyelashes and

eyebrows, which seemed to grow shorter the older I got. I had

very white regular teeth, and very small

hands and feet and waist; but I fretted because I was too fat to

slip into what is usually called “our stock size,” and

my complexion was by no means pale and interesting enough to please

me. From my gypsy tastes I preferred a picturesque toilette to a

merely smart one. I had beautiful hair, very long, thick and soft,

with five shades in it, and of a golden brown. My nose was

aquiline. I had all the material for a very good figure, and once a

sculptor wanted to sculpt me, but my mother would not allow it, as

she thought I should be ashamed of my figure later, when I had

fined down. I used to envy maypole, broomstick girls, who could

dress much prettier than I could. I was either fresh and wild with

spirits, or else melancholy and full of pathos. I wish I could give

as faithful a picture of my character; but we are apt to judge

ourselves either too favourably or too severely, and so I would

rather quote what a phrenologist wrote of me at this time:

“When Isabel Arundell loves, her affection will be

something extraordinary, her devotion great — in fact, too

great. It will be her leading passion, and influence her whole

life. Everything will be sacrificed for one man, and she will be

constant, unchangeable, and jealous of his affections. In short, he

will be her salvation or perdition! Her temper is good, but she is

passionate; not easily roused, but when violently irritated she

might be a perfect little demon. She is, however, forgiving. She is

full of originality and humour, and her utter naturalness will pass

for eccentricity. She loves society,

wherein she is wild and gay; when alone, she is thoughtful and

melancholy. She is ambitious, sagacious, and intellectual, and will

attract attention by a certain simple dignity, by a look in her eye

and a peculiar tone of her voice. To sum her up: Her nature is

noble, ardent, generous, honourable, and good-hearted. She has

courage, both animal and mental. Her faults are the noble and

dashing ones, the spicy kind to enlist one’s sympathies, the

weeds that spring from a too luxuriant soil.”

Thus wrote a professional phrenologist of me, and a friend who

was fond of me at the time endorsed it in every word. With regard

to the ambition, I always felt that if I were a man I should like

to be a great general or statesman, to have travelled everywhere,

to have seen and learnt everything; done everything; in fine, to be

the Man of the Day!

When I was between seventeen and eighteen years of age, we left

Furze Hall and went to London. The place in which we have passed

our youthful days, be it ever so dull, possesses a secret

charm.

I performed several pilgrimages of adieu to every spot connected

with the bright reminiscences of youth. I fancied no other fireside

would be so cosy, that I could sleep in no other room, no fields so

green. Those who know what it is to leave their quasi-native place

for the first time, never to return; to know every stick and stone

in the place for miles round, and take an everlasting farewell of

them all; to have one’s pet animals destroyed; to make a

bonfire of all the things that one does not want desecrated by

stranger hands; to sit on some height and

gaze on the general havoc, to reflect on what is, what has been,

and what may be in a strange world, amidst strange faces; to shake

hands with a crowd of poor old servants, peasants, and humble

friends, and not a dry eye to be seen, — those who have tasted

something of this will sympathize with my feelings then. “Ah,

miss,” the old retainers said, “we shall have no more

jolly Christmases; we shall have no beef, bread, and flannels next

year; the hall will not be decked with festoons of holly, there

will be no more music and dancing!” “No more

snapdragons and round games,” quoth the gamekeeper; and his

voice trembled, and I saw the tears in his eyes and in the eyes of

them all.

So broke up our little home in Essex, and we went our ways.

Chapter III

My First Season

(1849-1850)

Society itself, which should create

Kindness, destroys what little we have got.

To feel for none is the true social art

Of the world’s lovers.

Byron.

I was soon going through a London drilling. I was very much

pleased with town, and the novelty of my life amused me and

softened my grief at leaving my country home. I greatly disliked

being primmed and scolded, and I thought dressing up an awful bore,

and never going out without a chaperone a greater one. Some things

amused me very much. One thing was, that all the footmen with

powdered wigs who opened the door when one paid a visit were

obsequious if one came in a carriage, but looked as if they would

like to shut the door in one’s face if one came on foot.

Another was the way people stared at me; it used to make me laugh,

but I soon found I must not laugh in their faces.

We put our house in order; we got pretty dresses, and we left

our cards; we were all ready for the season’s campaign. I

made my début at a fancy ball at

Almack’s, which was then very exclusive. We went under the wing of

the Duchess of Norfolk.

I shall never forget that first ball. To begin at the beginning,

there was my dress. How a girl of the present day would despise it!

I wore white tarlatan over white silk, and the first skirt was

looped up to my knee with a blush rose. My hair, which was very

abundant, was tressed in an indescribable fashion by Alexandre, and

decked with blush roses. I had no ornaments; but I really looked

very well, and was proud of myself. We arrived at Almack’s

about eleven. The scene was dazzlingly brilliant to me as I

entered. The grand staircase and ante-chamber were decked with

garlands, and festoons of white and gold muslin and ribbons. The

blaze of lights, the odour of flowers, the perfumes, the diamonds

and the magnificent dresses of the cream of the British aristocracy

smote upon my senses; all was new to me, and all was sweet.

Julian’s band played divinely. My people had been absent from

London many seasons, so at first it seemed strange. But at

Almack’s every one knew every one else; for society in those

days was not a mob, but small and select. People did not struggle

to get on as people do now, and we were there by right, and to

resume our position in our circle. There is much more heart in the

world than many people give it credit for — at any rate in the

world of the gentle by birth and breeding. Every one had a hearty

welcome for my people, and some good-natured chaff about their

having “buried themselves” so long. I was at once taken

by the hand, and kindly greeted by many. Some great personage,

whose name I forget, gave a private supper,

besides the usual one, to which we were invited; and in those days

there were polkas, valses, quadrilles, and galops. Old stagers

(mammas) had told me to consider myself very lucky if I got four

dances, but I was engaged seven or eight deep soon after I entered

the ballroom, and had more partners than I could dance with in one

night. Of course mother was delighted with me, and I was equally

pleased with her: she looked so young and fashionable; and instead

of frightening young men away, as she had always done in the

country, she appeared to attract them, engage them in conversation,

and seemed to enjoy everything; she was such a nice chaperone. I

was very much confused at the amount of staring (I did not know

that every new girl was stared at on her first appearance); and one

may think how vain and incredulous I was, when I overheard some one

telling my mother that I had been quoted as the new beauty at his

club. Fancy, poor ugly me!

I shall not forget my enjoyment of that first ball. I had always

been taught to look upon it as the opening of Fashion’s fairy

gates to a paradise; nor was I disappointed, for, to a young girl

who has never seen anything, her first entrance into a brilliant

ballroom is very intoxicating. The blaze of light and colour, the

perfume of scent and bouquet, the beautiful dresses, the spirited

music, the seemingly joyous multitude of happy faces, laughing and

talking as if care were a myth, the partners flocking round the

door to see the new arrivals — all was delightful to me. But

then of course in those days we were not

born blasé, as the young people are to-day.

And I shall never forget my first opera. I shall always remember

the delights of that night. I thought even the crush-room lovely,

and the brilliant gaslight, the mysterious little boxes, with their

red-velvet curtains, filled with handsome men and pretty women,

which I think Lady Blessington describes as “rags of roues,

memoranda books of other women’s follies, like the last scene

of the theatre; they come out in gas and red flame, but do not

stand daylight.” I do not say that, but some of them

certainly looked so. The opera was La Sonambula, with

Jenny Lind and Gardoni. When the music commenced, I forgot I was on

earth; and, so passionately fond of singing and acting as I was, it

was not wonderful that I was quite absorbed by this earth’s

greatest delight. Jenny’s girlish figure, simple manner,

birdlike voice, so thrilling and so full of passion, her perfect

acting and irresistible lovemaking, were matchless. Gardoni was

very handsome and very stiff. The scene where Gardoni takes her

ring from her, and the last scene when he discovers his mistake,

and her final song, will ever be engraven on my memory; and if I

see the opera a thousand times, I shall never like it as well as I

did that night, for all was new to me. And after — only think,

what pleasure for me! — there came the ballet with the three

great stars Amalia Ferraris, Cerito, and Fanny Essler, whom so few

are old enough to remember now. There are no ballets nowadays like

those.

This London life of society and amusement was delightful to me

after the solitary one I had been leading in the country. I was

ready for anything, and the world and its excitement gave me no

time to hanker after my Essex home. The rust was soon rubbed off; I

forgot the clouds; my spirit was unbroken, and I lived in the

present scrap of rose-colour. They were joyous and brilliant days,

for I was exploring novelties I had only read or heard of. I went

through all the sight-seeing of London, and the (to me) fresh

amusement of shopping, visiting, operas, balls, and of driving in

Rotten Row. The days were very different then to what they are now:

one rose late, and, except a cup of tea, breakfast and luncheon

were one meal; then came shopping, visiting, or receiving. One went

to the Park or Row at 5.30, home to dress, and then off to dinner

or the opera, and out for the night, unless there was a party at

home. This lasted every day and night from March till the end of

July, and often there were two or three things of a night. I was

tired at first; but at the end of a fortnight I was tired-proof,

and of course I was dancing mad. The Sundays were diversified by

High Mass at Farm Street, and perhaps a Greenwich dinner in the

afternoon.

I enjoyed that season immensely, for it was all new, and the

life-zest was strong within me. But I could not help pitying poor

wall-flowers — a certain set of girls who come out every night,

who have been out season after season, and who stand or sit out all

night. I often used to say to my partners, “Do go and dance

with So-and-so"; and the usual rejoiner

was, “I really would do anything to oblige you, but I am sick

of seeing those girls.” In fact, we girls must not appear on

the London boards too often lest we fatigue these young coxcombs.

London, like the smallest watering-place, is full of cliques and

sets on a large scale, from Billingsgate up to the throne. The

great world then comprised the Court and its entourage,

the Ministers, and the Corps Diplomatique, the military,

naval, and literary stars, the leaders of the fashionable and

political world, the cream of the aristocracy of England;

and — at the time of which I write — the old Catholic

cousinhood clan used to hold its own. You must either have been

born in this great world, or you must have arrived in it through

aristocratic patronage, or through your talents, fame, or beauty.

Nowadays you only want wealth! There were some sets even then which

were rather rapid, which abolished a good deal of the tightness of

convenance, whose motto seemed to be savoir

vivre, to be easy, fascinating, fashionable, and dainty as

well as social.

I found a ballroom the very place for reflection; and with the

sentiment that I should use society for my pleasure instead of

being its slave, I sometimes obstinately would refuse a dance or

two, or sitting-out and talking, in order to lean against some

pillar and contemplate human nature, in defiance of my admirers,

who thought me very eccentric. I loved to watch the intriguing

mother catching a coronet for her daughter, and the father absorbed

in politics with some contemporary fogey; the old dandy with his

frilled shirt capering in a quadrille the

steps that were danced in Noah’s ark; the rouged old peeress,

whom you would not have taken to be respectable if you did not

happen to know her, flirting with boys. I saw other old ones, with

one foot in the grave, almost mad with excitement over cards and

dice, and every passion, except love, gleaming from their horrid

eyes. I saw the rivalry amongst the beauties. I noted the brainless

coxcomb, who comes in for an hour, leans against the door, twirls

his moustache, and goes out again — a sort of “Aw! the

Tenth-don’t-dance-young-man!”; the boy who asks all the

prettiest girls to dance, steps on their toes, tears their dresses,

and throws them down; the confirmed, bad, intriguing London girl,

who will play any game for her end; and the timid, delighted young

girl, who finds herself of consequence for the first time. I have

watched the victim of the heartless coquette — the young girl

gazing with tearful, longing eyes for the man to ask her to dance

to whom she has perhaps unconsciously betrayed her affection; she

in her innocence like a pane of glass, the other glorying in her

torture, dancing or flirting with the man in her sight, only to

glut her vanity with another’s disappointment. I have watched

the jealousy of men to each other, vying for a woman’s favour

and cutting each other out. I have heard mothers running down each

other’s daughters, dowagers and prudent spinsters casting

their eyes to heaven for vengeance on the change of

manners — even in the Forties! — on the licence of the day,

and the liberty of the age! I have heard them sighing for minuets

and pigtails, for I came between two

generations — the minuet was old and the polka was new; all

alike were polka mad, all crazed with the idea of getting up a new

fast style, but oh! lamblike to what it is now! I watched the last

century trying to accommodate itself to the present.

One common smile graced the lips of all — the innocent, the

guilty, the happy, and the wretched; the same colour on bright

cheeks, some of it real, some bought at Atkinson’s; and, more

wonderful still, the same general outward decorum, placidity,

innocence, and good humour, as if prearranged by general consent. I

pitied the vanity, jealousy, and gossip of many women. I classed

the men too: there were many good; but amongst some there were

dishonour and meanness to each other, in some there were coarseness

and brutality, and in some there was deception to women; some were

so narrow-minded, so wanting in intellect, that I believed a horse

or a dog to be far superior. But my ideal was too high, and I had

not in those days found my superior being.

I met some very odd characters, which made one form some rather

useful rules to go by. One man I met had every girl’s name

down on paper, if she belonged to the haute volée, her

age, her fortune, and her personal merits; for he said, “One

woman, unless one happens to be in love with her, is much the same

as another.” He showed me my name down thus: “Isabel

Arundell, eighteen, beauty, talent and goodness,

original — chief fault £0 0s. 0d.!”

Then he showed me the name of one of my friends: “Handsome, age

seventeen, rather missish, £50,000; she

cannot afford to flirt except pour le bon motif, and I

cannot afford, as a younger brother, to marry a girl with £50,000.

She is sure to have been brought up like a duchess, and want the

whole of her money for pin-money — a deuced expensive thing is

a girl with £50,000!” Then he rattled on to others. I told

him I did not think much of the young men of the day. “There

now,” he answered, “drink of the spring nearest to you,

and be thankful; by being too fastidious you will get

nothing.”

I took a great dislike to the regular Blue Stocking; I can

remember reading somewhere such a good description of her:

“One who possesses every qualification to distinguish herself

in conversation, well read and intelligent, her manner cold, her

head cooler, her heart the coldest of all, never the dupe of her

own sentiments; she examined her people before she adopted them, a

necessary precaution where light is borrowed.”

A great curiosity to me were certain married people, who were

known never to speak to each other at home, but who respected the

convenances of society so much that even if they never met

in private they took care to be seen together in public, and to

enter evening parties together with smiling countenances. Somebody

writes:

Have they not got polemics and reform,

Peace, war, the taxes, and what is called the Nation,

The struggle to be pilots in the storm,

The landed and the moneyed speculation,

The joys of mutual hate to keep them warm

Instead of love, that mere hallucination?

What a contrast women are! One woman is “fine enough to

cut her own relations, too fine to be seen in the usual places of

public resort, and therefore of course passes with the vulgar for

something exquisitely refined.” Another I have seen who would

have sacrificed all London and its “gorgeous mantle of purple

and gold” to have wedded some pale shadow of friendship,

which had wandered by her side amid her childhood’s dreary

waste. And oh! how I pity the many stars who fall out of the too

dangerously attractive circle of society! The fault there seems not

to be the sin, but the stupidity of being found out. I say one

little prayer every day: “Lord, keep me from

contamination.” I never saw a woman who renounced her place

in society who did not prove herself capable of understanding its

value by falling fifty fathoms lower than her original fall. The

fact is, very few people of the world, especially those who have

not arrived at the age of discretion, are apt to stop short in

their career of pleasure for the purpose of weighing in the balance

their own conduct, enjoyments, or prospects; in short, it would be

very difficult for any worldly woman to be always stopping to

examine whether she is enjoying the right kind of happiness in the

right kind of way, and, once fallen, a woman seems to depend on her

beauty to create any interest in her favour. I knew nothing of

these things then; and though I think it quite right that women

should be kept in awe of certain misdemeanours, I cannot understand

why, when one, who is not bad, has a misfortune, other women should

join in hounding her down, and at the same

time giving such licence to really bad women, whom society cannot

apparently do without. ’Tis “one man may steal a horse,

and another may not look over the hedge.” If a woman fell

down in the mud with her nice white clothes on, and had a journey

to go, she would not lie down and wallow in the mud; she would jump

up, and wash herself clean at the nearest spring, and be very

careful not to fall again, and reach her journey’s end

safely. But other women do not allow that; they must haul out

buckets of the mud, and pour it over the fallen one, that there may

be no mistake about it at all. Then men seem to find a wondrous

charm in poaching on other men’s preserves (though a poacher

of birds gets terrible punishments, once upon a time hanging), as

if their neighbours’ coverts afforded better shooting than

their own manors.

When I went to London, I had no idea of the matrimonial market;

I should have laughed at it just as much as an unmarrying man

would. I was interested in the fast girls who amused themselves at

most extraordinary lengths, not meaning to marry the man; and at

the slower ones labouring day and night for a husband of some sort,

without any success. I heard a lady one day say to her daughter,

“My dear, if you do not get off during your first season, I

shall break my heart.” Our favourite men joined us in walks

and rides, came into our opera-box, and barred all the waltzes; but

it would have been no fun to me to have gone on as some girls did,

because I had no desire to reach the happy goal, either properly or

improperly. Mothers considered me crazy,

and almost insolent, because I was not ready to snap at any good

parti ; and I have seen dukes’ daughters gladly

accept men that poor humble I would have turned up my nose at.

What think’st thou of the fair Sir Eglamour?

As of a knight well spoken, neat and fine,

But were I you he never should be mine.

Lots of such men, or mannikins, affected the season, then as

now, and congregated around the rails of Rotten Row. I sometimes

wonder if they are men at all, or merely sexless

creatures — animated tailors’ dummies. Shame on them thus

to disgrace their manhood! ’Tis man’s work to do great

deeds! Well, the young men of the day passed before me without

making the slightest impression. My ideal was not among them. My

ideal, as I wrote it down in my diary at that time, was this:

“As God took a rib out of Adam and made a woman of it, so

do I, out of a wild chaos of thought, form a man unto myself. In

outward form and inmost soul his life and deeds an ideal This

species of fastidiousness has protected me and kept me from

fulfilling the vocation of my sex — breeding fools and

chronicling small beer. My ideal is about six feet in height; he

has not an ounce of fat on him; he has broad and muscular

shoulders, a powerful, deep chest; he is a Hercules of manly

strength. He has black hair, a brown complexion, a clever forehead,

sagacious eyebrows, large, black, wondrous eyes — those strange

eyes you dare not take yours from off them — with long

lashes. He is a soldier and a man

; he is accustomed to command and to be obeyed. He frowns on the

ordinary affairs of life, but his face always lights up warmly for

me. In his dress he never adopts the fopperies of the day, but his

clothes suit him — they are made for him, not he for them. He

is a thorough man of the world; he is a few years older than

myself. He is a gentleman in every sense of the word — not only

in manners, dress, and appearance, but in birth and position, and,

better still, in ideas and actions; and of course he is an

Englishman. His religion is like my own, free, liberal, and

generous-minded. He is by no means indifferent on the subject, as

most men are; and even if he does not conform to any Church, he

will serve God from his innate duty and sense of honour. The great

principle is there. He is not only not a fidgety, strait-laced, or

mistaken-conscienced man on any subject; he always gives the mind

its head. His politics are conservative, yet progressive. His

manners are simple and dignified, his mind refined and sensitive,

his temper under control; he has a good heart, with common sense,

and more than one man’s share of brains. He is a man who owns

something more than a body; he has a head and heart, a mind and

soul. He is one of those strong men who lead, the mastermind who

governs, and he has perfect control over himself.

“This is the creation of my fancy, and my ideal of

happiness is to be to such a man wife, comrade,

friend — everything to him, to sacrifice all for him, to follow

his fortunes through his campaigns, through

his travels, to any part of the world, and endure any amount of

roughing. I speak of the ideal man ’tis true, and some may

mock and say, ‘Where is the mate for such a man to be

found?’ But there are ideal women too. Such a man only will I

wed. I love this myth of my girlhood — for myth it

is — next to God; and I look to the star that Hagar the gypsy

said was the star of my destiny, the morning star, which is the

place I allot to my earthly god, because the ideal seems too high

for this planet, and, like the philosopher’s stone, may never

be found here. But if I find such a man, and afterwards discover he

is not for me, then I will never marry. I will try to be near him,

only to see him, and hear him speak; and if he marries somebody

else, I will become a sister of charity of St. Vincent de

Paul.”

Chapter IV

Boulogne: I Meet My Destiny

(1850-1852)

Was’t archer shot me, or was’t thine eyes?

Alf Laylah wa Laylah

(Burton’s “Arabian Nights”).

The season over (August, 1850), change of air, sea-bathing,

French masters to finish our education, and economy were loudly

called for; and we turned our faces towards some quiet place on the

opposite shores of France, and we thought that Boulogne might suit.

We were soon ready and off.

We had a pleasant but rough passage of fifteen hours from

London. While the others were employed in bringing up their

breakfasts, I sat on deck and mused. Suddenly I remembered that

Hagar had told me I should cross the sea, and then I wondered why

we had chosen Boulogne. I was leaving England for the first time; I

knew not for how long. What should I go through there, and how

changed should I come back? I had gone with a light heart. I was

young then; I loved society and hated exile. I had written in my

diary only a little time before: “As for me, I am never

better pleased than when I watch this huge

game of chess, Life, being played on that extensive chessboard,

Society.” I never felt so patriotic as that first morning on

sea when the white cliffs faded from my view. We never appreciate

things until we lose them, and I thought of what the feelings of

soldiers and sailors must be, going from England and returning

after years of absence.

At length the boat stopped at the landing-place at Boulogne, and

we were driven like a flock of sheep between two ropes into a

papier-maché -looking building, whence we were put into a

carriage like a bathing-machine, and driven through what I took to

be mews, but which were in reality the principal streets. I

recognize in this reflection the prejudiced London Britisher, the

John Bull; for in reality Boulogne was a most picturesque town, and

our way lay through most picturesque streets. After driving up the

hilly street, and under an archway, in the old town, we came to a

good, large house like a barn, No. 4, Rue des Basses Chambres,

Haute Ville, Boulogne-sur-Mer. The rooms were chiefly furnished

with bellows and brass candlesticks; there was not the ghost of an

armchair, sofa, ottoman, or anything comfortable; and the only

thing at all cheery was our kinswoman, Mrs. Edmond Jerningham, who,

apprised of our arrival, had our fires lighted and beds made. She

was cutting bread-and-butter and preparing tea for us when we came

in, and had ready for us a turkey the size of a fine English

chicken. This banquet over, we all turned into bed, and slept

between the blankets.

Next morning our boxes were still detained at the custom-house, and my brothers and sisters and myself

got some bad tea and some good bread-and-butter, and sat round in a

circle on the floor in our night-gowns, with our food in the

middle. Shortly after we heard a hooting, laughing, and wrangling

in a shrill key, “Coralie, Rosalie, Florantine, Celestine,

Euphrosine!” so I pricked up my ears in the hopes of seeing

some of those pretty, well-dressed, piquante little

soubrettes of whom we had heard mother talk, when in

rolled about a dozen harpies with our luggage. At first I did not

feel sure whether they were men or women; they had picturesque

female dresses on, but their manners, voices; language, and

gestures were those of the lowest costermongers. They spoke to me

in patois, which I did not understand, and seemed

surprised to see us all in our nightgowns, forgetting that we had

little else to put on till they had brought the luggage. I gave

them half a crown, which they appeared to think a great deal of

money, and it inspirited them greatly. They danced about me,

whirled me round, and in five minutes one had decked me up in a red

petticoat, another arrayed me in her jacket, and a third clapped

her dirty cap on my head, and I was completely attired à la

marine. I felt so amused by the novelty of the thing that I

forgot to be angry at their impertinence, and laughed as heartily

as they did.

When they were gone, we set to work and unpacked and dressed,

and by the afternoon were as comfortable as we could make

ourselves; but we were thoroughly wretched, though mother kept

telling us to look at the beautiful sky,

which was not half as blue or bright as on the other side of the

water. We sauntered out to look at the town. I own my first

impressions of France were very unfavourable; Boulogne looked to me

like a dirty pack of cards, such as a gypsy pulls out of her pocket

to tell your fortune with. The streets were irregular, narrow,

filthy, and full of open gutters, which we thought would give us

the cholera. The pavement was like that of a mews; the houses were

unfurnished; the sea was so far out from our part of the town that

it might as well not have been there — and such a dirty,

ugly-looking sea too, we thought! The harbour was full of

poisonous-looking smelling mud, and always appeared to be low

water. The country was dry, barren, and a dirty brown (it was a hot

August); the cliffs were black; and there was not a tree to be

seen — I used to pretend to get under a lamp-post for shade.

Every now and then we had days of fine weather, with clouds of dust

and sirocco, or else pouring rain and bleak winds. From

mother’s talk of the Continent we expected at least the

comforts of Brighton with the romance of Naples; and I shall never

forget our feelings when we were told that, after Paris, Boulogne

was the nicest town in France. Now I imagine that ours are the

feelings of every narrow-minded, prejudiced John Bull Britisher the

first time he lands abroad. It takes him some little time to

thoroughly appreciate all the good things that he does get abroad,

and to be fascinated with the picturesqueness, and then often he

returns home unwillingly.

We had a cheap cook, so that our dinners would have been scarcely served up in my father’s

kennel at home. When I had eaten what I could pick out by dint of

shutting my eyes and forcing myself to get it down, I used to lie

down daily on a large horsehair sofa, such as one sees in a

tradesman’s office, and sometimes cry till I fell asleep; I

felt so sorry for us all.

The most interesting people in Boulogne were the

poissardes, or fisherwomen; they are of Spanish and

Flemish extraction, and are a clan apart to themselves. They are so

interesting that I wonder that no one has written a little book

about them. They look down on the Boulognais; they are a fine race,

tall, dark, handsome, and have an air of good breeding. Their dress

is most picturesque. The women wear a short red petticoat, dark

jacket, and snowy handkerchief or scarf, and a white veil tied

round the head and hanging a little behind. On fête days

they add a gorgeous satin apron. These costumes are expensive.

Their long, drooping, gold earrings and massive ornaments are

heirlooms, and their lace is real. The men wear great jack-boots

all the way up their legs, a loose dark jacket, and red cap; they

are fine, stalwart men. They had a queen named Carolina, a

handsome, intelligent woman, with whom I made great friends; and

also a captain, who had a daughter so like me that when I used to

go to the fish-market at first they used to chaff me, thinking she

had dressed up like a lady for fun. They also have their different

grades of society; they have their own church, built by themselves,

their separate weddings, funerals, and christenings. They do not marry out of their own

tribe or associate with the townspeople. Their language has a

number of Spanish and Latin words in it. They have a strict code of

laws, live in a separate part of the town on a hill, are never

allowed to be idle, and are remarkable for their morality, although

by the recklessness of the conduct and talk of some of the commoner

ones you would scarcely believe it. If an accident does occur, the

man is obliged to marry the girl directly. The upper ones are most

civil and well spoken, and all are open-hearted and not grasping.

There is a regular fleet of smacks. The men are always out fishing.

The women do all the work at home, as well as shrimping, making

tackle, marketing, getting their husbands’ boats ready for

sea, and unloading them on return; and they are prosperous and

happy. The smacks are out for a week or ten days, and have their

regular turn. They have no salmon, and the best fish is on our side

of the water. The lowest grade of the girls, who serve as kinds of

hacks to the others, are the shrimping girls; they are as vulgar as

Billingsgate and as wild as red Indians. You meet them in parties

of thirty or forty, with their clothes kilted nearly up to their

waists and nets over their backs. They sing songs, and are sure to

insult you as you pass; but they make off at a double quick trot at

the very name of Queen Carolina.

At Boulogne the usual lounge, both summer and winter, was the

Ramparts, which were extremely pretty and picturesque. The Ramparts

were charming in summer, with a lovely view of the town; and a row

down the Liane, or a walk along its banks,

was not to be despised. There were several beautiful country walks

in summer. The peasants’ dances, called guinguettes,

were amusing to look at. The hotels and table

d’hôtes were not bad. The ivory shops in the town were

beautiful; the bonnets, parasols, and dresses very chic; the

bonbons delicious. The market was a curious, picturesque little

scene. There were pretty fêtes, religious and profane, and

a capital carnival.

The good society we collected around us; but it was small, and

never mixed with the general society. The two winters we were there

were gay; there was a sort of agreeable laissez aller

about the place, and the summers were very pleasant. But mother

kept us terribly strict, and this was a great stimulant to do wild

things; and though we never did anything terrible, we did what we

had better have left alone. For instance, we girls learned to

smoke. We found that father had got a very nice box of cigars, and

we stole one. We took it up to the loft and smoked it, and were

very sick, and then perfumed ourselves with scent, and appeared in

our usual places. We persevered till we became regular smokers, and

father’s box of cigars disappeared one by one. Then the

servants were accused; so we had to come forward, go into his den,

make him swear not to tell, and confided the matter to him. He did

not betray us, as he knew we should be almost locked up, and from

that time we smoked regularly. People used to say, “What

makes those Arundell girls so pale ? They must dance too

much.” Alas, poor things ! it was just the want of these innocent recreations that drove us

to so dark a deed !

I have already said that we were taken to Boulogne for masters

and economy. Our house in the Haute Ville was next to the Convent,

and close to the future rising — slowly rising — Notre